Insects under threat: the role of natural history collections in biodiversity conservation

A selection of nine-spotted ladybug specimens from the Cornell University Insect Collection. This beetle was considered extinct in New York by 1999.

By Megan Barkdull, Ph.D. Candidate, Cornell University, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

Published August 10, 2022

The nine-spotted ladybug was a beautiful, orange-and-black spotted beetle, so common that it was designated New York’s state insect in the 1980s. But by 1999, the species was considered extinct, and could no longer be found anywhere in the state.

We’ll come back to the nine-spotted ladybug later, but it’s far from the only insect species to face extinction. Our planet is currently experiencing its sixth mass extinction. One third of the planet’s 900,000 insect species are endangered, and many of those could be lost in coming decades.

Why is insect biodiversity under threat? Largely, insect declines are a result of human impacts on ecosystems. One major factor is how we farm. Intensive agriculture cultivates huge fields of single crops like corn or soy which are heavily treated with pesticides. This destroys insect habitats and directly kills many species. Insect declines are also driven by climate change. Rising temperatures and changes to normal patterns of rainfall make ecosystems inhospitable to local insects. In addition to the major impacts of agriculture and climate change, other causes like invasive species also lead to insect declines.

You may have already observed signs of insect declines locally. Perhaps you’ve noticed fewer monarch butterflies flitting about than in past summers. And indeed, monarch butterfly populations have plummeted more than 80% in the last 20 years. Or maybe, when taking road trips, you’ve noted that your windshield doesn’t get coated with bugs like it used to. But beyond a loss of beauty, or a reduction in summer car wash spending, why care about global losses of insect biodiversity?

Insects provide many economically indispensable services to humans. You probably know that bees and other pollinators pollinate our food crops. You might not have known that the services provided by insect pollinators are valued at as much at $6.5 billion each year! And while pollination might be the best known example, insects provide other valuable services too. For instance, without dung beetles to bury cowpats, cattle waste renders pastures unpalatable, makes cows sick, and causes nutrient runoff that pollutes local waterways. The presence of dung beetles reduces sickness, leads to better pasture quality, and helps recycle nutrients into soil, strengthening our farms and ranches. Insects can even give us new medicines: chemicals from wasp venoms, butterfly wings, and other sources are being studied as potential neurological and anti-cancer drugs. Every time an insect species goes extinct, we lose potentially useful biological information along with it.

Clearly the loss of global insect biodiversity will have major, negative impacts on humans and life on Earth more broadly. Motivated by this understanding, scientists across the globe are working to understand how we can slow, stop or reverse insect declines.

Natural history collections play a critical role in this effort. To understand how scientists use collections, it helps to understand the different parts of a natural history collection specimen. Specimens are made of two parts: the physical object, usually an insect preserved on a pin or in a storage vial, and the label that accompanies the physical object. While you might think that the preserved insect is more important than its label, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Accurate, complete label data let scientists determine when and where an insect was collected, can record the type of habitat it was in, and let scientists associate a single insect with other insects caught at the same time or in the same place.

A pinned caterpillar with labels, demonstrating the combination of physical object and label data that together make up a natural history collection specimen.

A pinned beetle with labels, demonstrating the combination of physical object and label data that together make up a natural history collection specimen.

Scientists can also get a treasure trove of information from physical specimens. Of course, there’s information about insect morphology: sizes, shapes, colors, patterns. Sometimes, insect specimens can even be microCT scanned to get information about their internal organs and anatomy! And in the past few decades, we have unlocked a whole new source of data stored in natural history collections: DNA. Using careful techniques, scientists can retrieve DNA from specimens. This can be possible even for specimens that are centuries old. Genetic data helps us better understand insect biodiversity both past and present.

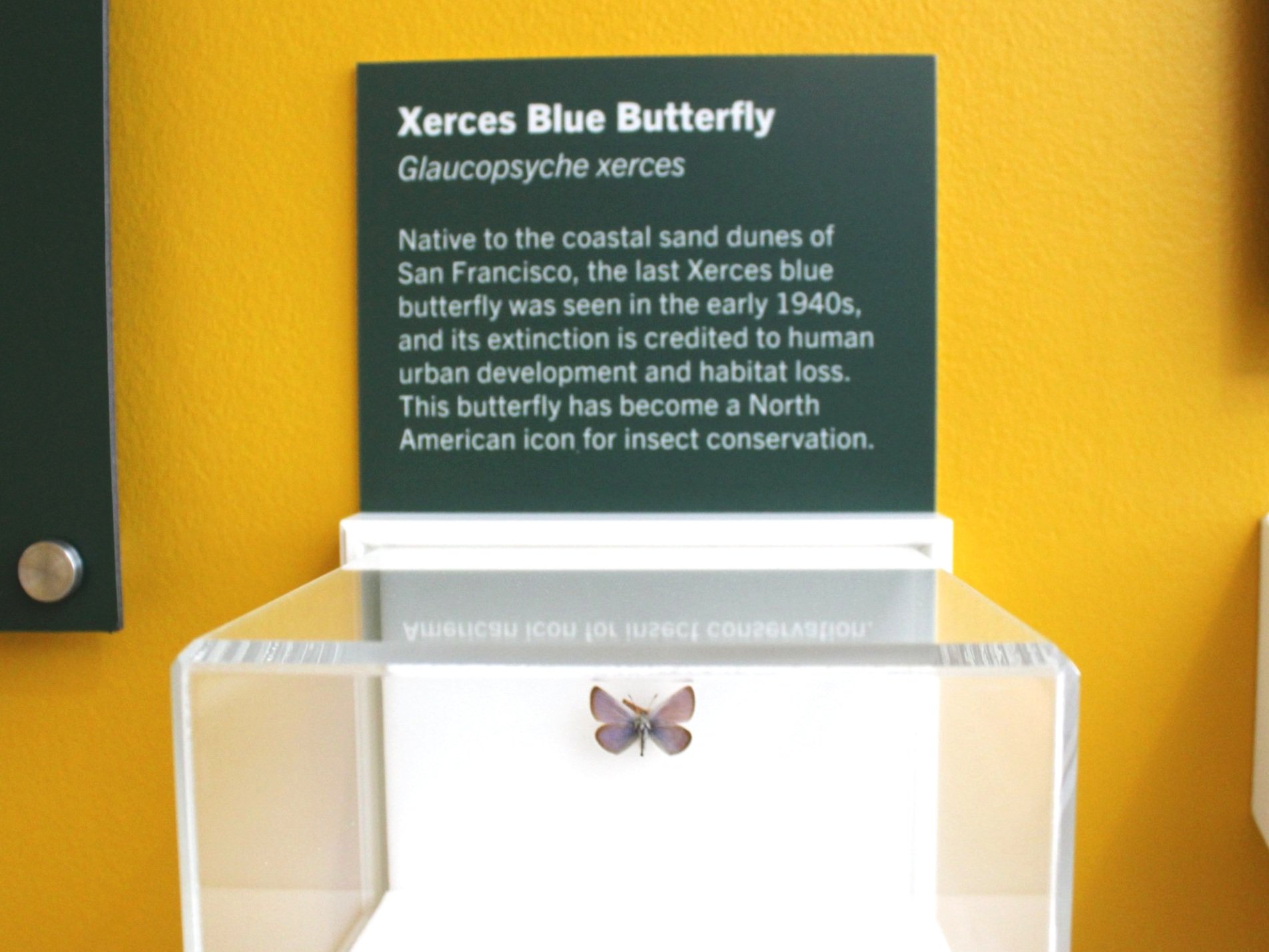

Xerces Blue Butterfly specimen temporarily on display in the Museum of the Earth’s exhibit Six-Legged Science: Unlocking the Secrets of the Insect World (2022)

All of this data is put to use by biodiversity researchers in many ways. For example, sometimes it can be hard to tell whether an insect that has gone extinct was really a unique species, or whether it was a sub-variety of a more common species. This was the case for the Xerces Blue, a small blue butterfly native to the San Francisco coast. Urban development drove it to extinction in the 1940s. But was it a unique species? Or was the Xerces blue just a subspecies of the much more common Silvery blue?

In 2021, researchers were able to provide an answer. They extracted DNA from a 93-year old Xerces blue specimen, and compared that DNA to DNA from closely related butterflies. They found that the Xerces blue was genetically different enough to be considered a separate species. Sadly, that also confirms that the Xerces blue is extinct. This kind of research demonstrates the importance of protecting small, vulnerable populations and their habitats in the future.

Sometimes, researchers working with natural history collections are able to help protect biodiversity in very immediate, concrete ways. In 2018, a sniffer dog at the Toronto International Airport stopped a man flying in from Russia. What had the beagle smelled in his luggage? More than 5,000 live leeches!

Some medicinal leech species are used for unproven naturopathic practices, and fetch high prices on the black market. Human overharvesting has caused populations of the leech species Hirudo verbana to plummet. To conserve the species, it is protected by international law. Legally, medicinal leeches cannot be imported without a permit. When the Canadian authorities intercepted the smuggled leeches, one important question was whether the leeches had been harvested from a wild, endangered population, or if they had come from a leech breeding facility in Europe. The leeches’ source would tell us how much of a problem this particular poaching event was for wild populations.

So where do natural history collections come into this? To figure out where the leeches came from, Canadian authorities sent some of them to researchers at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. There, a team of researchers including myself, used DNA from the leeches’ guts to figure out what kinds of animal blood they had fed on. If it was all cow blood? Well, that’s what leech breeding facilities use, so they were probably captive-bred. If they were full of blood from wild animals? Then the leeches had probably been poached from a threatened wild population.

A jar of preserved leeches, a subset of the 5,000 leeches smuggled internationally to Toronto International Airport.

That’s exactly what we found. The smuggled leeches had fed on pygmy cormorants, tree frogs, and other wild animals. The DNA in the leech guts let us figure out that the leeches were wild harvested from a wetland somewhere in Eastern Europe. By combining the expertise of museum-based scientists with international legal protections, the conservation community can use this information to protect threatened leeches moving forward.

Finally, let’s circle back to the nine-spotted ladybug. Are these beautiful beetles another example of too little, too late, like the Xerces blue butterfly? Happily, no! In 2011, community scientists collaborating with Cornell’s Lost Ladybug project rediscovered the nine-spotted ladybug on a farm on Long Island, demonstrating that the ladybug has not been lost forever. We have a second chance to protect this iconic species. Since then, scientists have used a combination of wild-caught ladybugs and ladybug specimens from the Cornell University Insect Collection to better understand why the species became so rare. They’ve found that the nine-spotted ladybug may be outcompeted for food by the seven-spotted ladybug, causing the population declines that have been observed.

The extinct Xerces blue, smuggled medicinal leeches, and rediscovered nine-spotted ladybug are just a few examples of how conservation research is fueled by natural history collections. To continue this important work, collections need our support. Collections need ongoing funding to protect their specimens, support researcher salaries, and fund research and collecting trips. You can help by calling on funding agencies to prioritize natural history collection funding in their budgets. Another way you can support collections is by engaging with their outreach events and exhibits, spreading the word about collections’ importance. Who knows- a childhood visit to the Museum of the Earth’s exhibit Six-Legged Science: Unlocking the Secrets of the Insect World could be the first step on the road to a career in biodiversity research.

Sources to learn more:

More about the nine-spotted ladybug: https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2011/10/found-new-york-long-last-nine-spotted-ladybugs

NPR story on monarch butterfly declines: https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2011/10/found-new-york-long-last-nine-spotted-ladybugs

Nature Conservancy write-up about dung beetles: https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/where-we-work/latin-america/stories-in-latin-america/biodiversity-dung-beetle/

Write-up on Xerces blue research: https://news.wttw.com/2021/07/20/field-museum-scientists-use-dna-unlock-extinction-mystery-xerces-blue-butterfly

BBC article about smuggled leeches: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-48434072

Check out the Museum of the Earth temporary exhibit in collaboration with Cornell University Insect Collection, Six-Legged Science: Unlocking the Secrets of the Insect World !