Virtual Collections on the Digital Atlas of Ancient Life

Note: This post was originally published in the iDigBio Research Spotlight newsletter in November 2019. It is reprinted here with permission of iDigBio and includes some minor changes relative to the original.

by Jonathan R. Hendricks, Jaleigh Q. Pier, and Elizabeth J. Hermsen

Last updated January 16, 2020

Physical specimens play a central role in teaching students about natural history because they provide tangible connections to the natural world that make concepts like homology and evolutionary modification real. Students in biology and paleontology classes often learn about the diversity and evolution of organismal form through examination and comparison of specimens representing different clades and evolutionary grades of organisms. Specimens in teaching collections can even inspire awe in students. In a paleontology class, for example, a 500-million-year-old trilobite fossil might be the oldest object that a student has ever held.

Trilobite fossils in the teaching collection at the Paleontological Research Institution.

While critical to learning, collections of teaching specimens pose challenges. We will focus our attention here on some of the limitations of paleontological teaching collections, although some of these limitations also apply to teaching collections in biological fields. Some of the major challenges include:

Access: Teaching collections are often available only for the duration of a lab period, and thus relatively inaccessible to students for further study. They may be housed in rooms that students cannot use outside of regular classroom hours for safety and security reasons, or they may be stored separately and brought out just for lab. Allowing students to take fossils on loan to study, while a potential solution, would be unfair to their classmates and would invite loss or damage of specimens that might be difficult to replace. In museum settings, teaching collections are often used in outreach programs. Children may become inspired by the specimens they learn about, with limited ways to further foster those interests immediately afterwards.

Scope: Teaching collections typically do not provide a representative sampling across taxa or across geological time. For example, common fossils that can be found in regional outcrops may be overrepresented, whereas other important taxa and time intervals that are not locally available may be represented by few or no specimens. Furthermore, some material may simply be too fragile or rare to include in a teaching collection.

Quality: Even where specimens are available, key morphological features may not be well preserved in teaching samples, either for taphonomic reasons or due to wear and tear after decades of rough classroom handling.

Resources: Many instructors who teach in traditional classroom settings have only a handful of specimens to share with their students because the resources do not exist to establish and maintain an adequate teaching collection. Even if such a collection has been established, limited resources may make it difficult to replace lost, damaged, or deteriorated specimens, or to add to the collection to make it more complete.

Online learning: A significant amount of student learning now takes place on the web, outside of classroom settings; online learning is even increasingly prevalent on traditional college campuses. Unless there is a nearby natural history museum, instructors of online courses simply do not have a way to share real fossil specimens with their students, other than by directing them to photographs on websites (when available). Even then, the photographs themselves may be limited in breadth and quality.

In order to overcome some of these limitations, we have developed a Virtual Collection of interactive, digital, 3D models of fossil and modern specimens from the research collections of the Paleontological Research Institution (PRI), the public exhibits of its Museum of the Earth, and the paleobotanical teaching collections of Cornell University. Examples of two such 3D models (a trilobite and a Megalodon shark tooth) are shown below; you may interact with them by clicking on the triangular “play” button.

These models have been created as part of the Digital Atlas of Ancient Life project, which is supported by the National Science Foundation. This Virtual Collection of specimens can be viewed at https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/vc/. Specimens are arranged into virtual “drawers,” sorted into major taxonomic categories. The models represent most of the paleontologically significant plant and animal groups in the macrofossil record. Several other collections arranged around non-taxonomic themes (e.g., trace fossils, fossil preservation, and Devonian Fossils of New York) have also been developed.

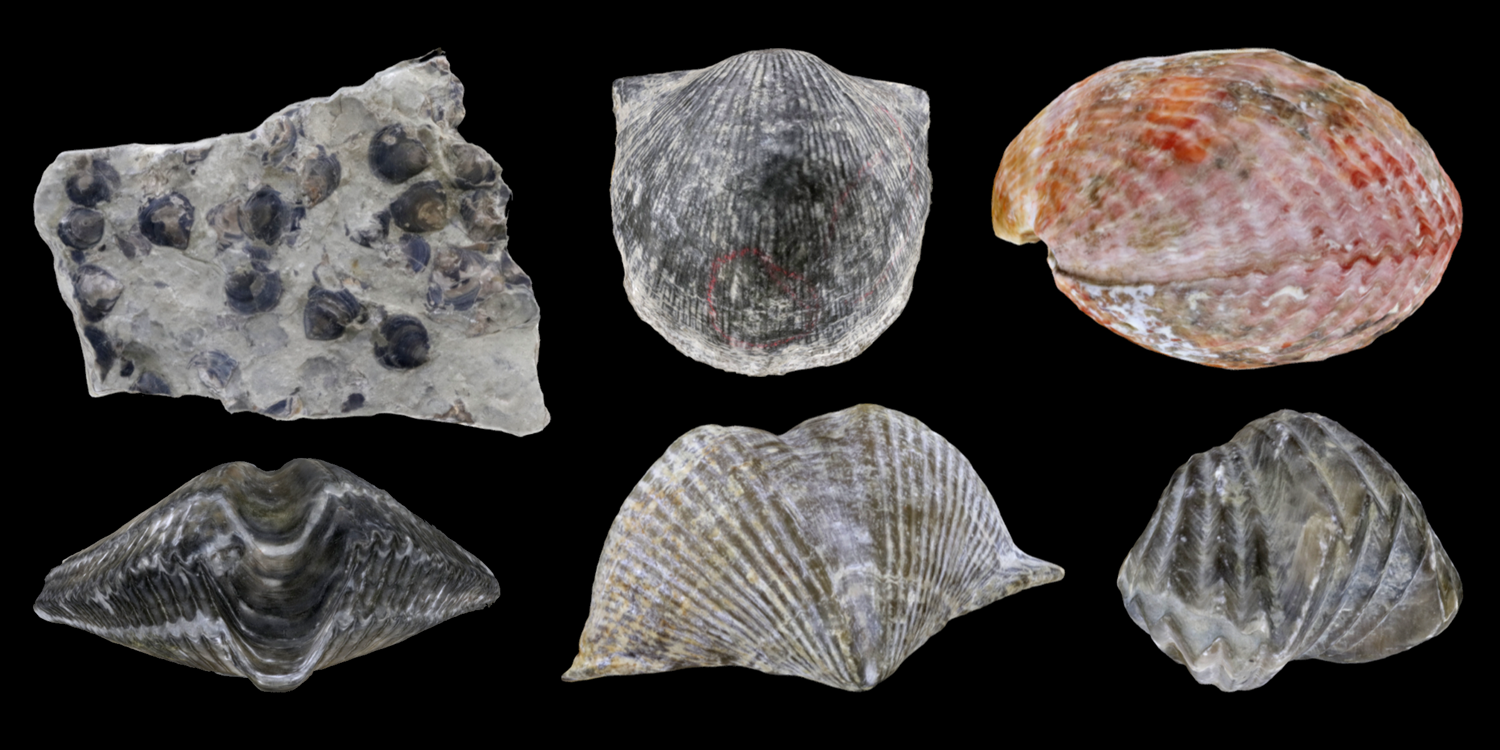

Examples of 3D models of fossil and modern (upper right) brachiopod shells.

Each virtual specimen in the collection was generated using photogrammetry, an inexpensive and efficient way to make 3D models. In order to make a model, over 100 images of a specimen are captured from all angles, and sophisticated computer software is then used to create a 3D model from those images. A detailed, cookbook-style user guide by Emily Hauf explains how we created our 3D models at PRI: https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/methods-techniques/photogramme.... Once developed, each 3D model is posted to the Digital Atlas of Ancient Life Sketchfab account (https://sketchfab.com/DigitalAtlasOfAncientLife), where it is publicly shared. Models can be viewed, manipulated (for example, users can turn and zoom in and out on specimen models), downloaded, 3D printed, and used to create animated GIFs. Each model has a Creative Commons license, which places few restrictions on its use. The Virtual Collections on the Digital Atlas of Ancient Life include embedded versions of the models hosted by Sketchfab.

What advantages do such Virtual Collections of 3D specimen models have for teaching compared with real fossil specimens? The most obvious is that they can be studied outside of the classroom by anyone with an internet connection. Furthermore, the 3D models themselves can be annotated in Sketchfab, allowing key features to be identified in order to facilitate student learning.

The models can be projected and manipulated at full-screen size in classroom presentations, allowing for their use in lecture or to provide guidance to students during labs. They also allow fragile, rare, and/or scientifically important specimens to be shared with students without fear of damage or loss. Many of the specimens in the Virtual Collections are among the best-of-the-best samples from collections and exhibits, thus representing high-quality specimens that typically would not be used in a classroom setting. As just one example, the collections include a 3D model of an extraordinary specimen of the heteromorph ammonoid Diplomoceras maximum that was collected from the Cretaceous of Antarctica and is on display at the Museum of the Earth.

Developing Virtual Collections from the physical holdings of a large paleontological collection ensures that a wide range of taxa and styles of preservation can be captured, which is beyond the scope of most small teaching collections. Thus, students from all levels and learning styles can interact (albeit virtually) with a much greater variety of fossil specimens than would typically be available to them. To date, we have created over 500 3D models of PRI specimens, nearly all of which have been added to our Virtual Collections. Many of these 3D models are being integrated into our growing open access, online Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life paleontology textbook (https://www.digitalatlasofancientlife.org/learn/), allowing students to view and manipulate virtual fossil specimens as they learn about them.

While we would never argue that virtual fossil specimens should supplant the real thing for teaching and learning, we argue they provide a powerful supplement to traditional collections. Virtual specimens are the “next best thing” when real fossil specimens are not otherwise available for students to study.