Seven things you can do about climate change if you don't have a lot of time

Dr. Ingrid H. H. Zabel, Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York 14850

Published November 16, 2022

Do you want to do something about climate change, but you don’t have the time? You’re not alone. And you’re not out of luck. Here are seven things you can do that won’t take up much of your time at all.

1. Write to your local, state, or federal representative, urging them to support climate action

TIME: 20 minutes per letter (5 minutes to look up how to contact your rep; 15 minutes to write the letter)

Your representative needs to know your views about climate change. If you voted for them and you feel like they represent your views, your letter will let them know that you support them in pushing for legislative action, and helps give them courage.

If you didn’t vote for them or feel like they don’t represent your views, you can try to educate and influence them. If enough of their constituents share views similar to yours and speak up, your rep might feel pressure to change their stance.

To find your federal and state representatives, including links to their websites where you can email them, try Openstates.org.

IMPACT: hard to quantify in terms of emissions prevented, but potentially enormously impactful if a lot of people do this!

BONUS: You can amplify your voice with little time investment. Did you write to your U.S. congressional rep? Take another few minutes to send the same letter to your state and local reps, too.

2. Adjust your thermostat

TIME: 1 minute per day (or 1 minute per season with a programmable thermostat)

Image: Franz von Pocci, 1845, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Put on a sweater and slippers to keep yourself warm in the winter instead of turning up your thermostat. Who says hats are only for wearing outdoors? Go retro and wear a nightcap like your ancestors probably did hundreds of years ago.

It takes very little time to adjust your thermostat, and you only have to do it once per season if you have a programmable thermostat. Learn more about programmable thermostats from the U.S. Department of Energy.

IMPACT: According to a study [1] from Oak Ridge National Laboratory, if everyone in the U.S. changed their thermostat by just 1°F (lowering in winter and raising in summer), we would reduce our annual carbon emissions by 7.2 million metric tons. That’s equivalent to burning about 800,000,000 fewer gallons of gasoline (to make this calculation, see the U.S. EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator).

BONUS: you’ll save money by using less energy.

3. Eat less meat

TIME: less than 1 minute per day

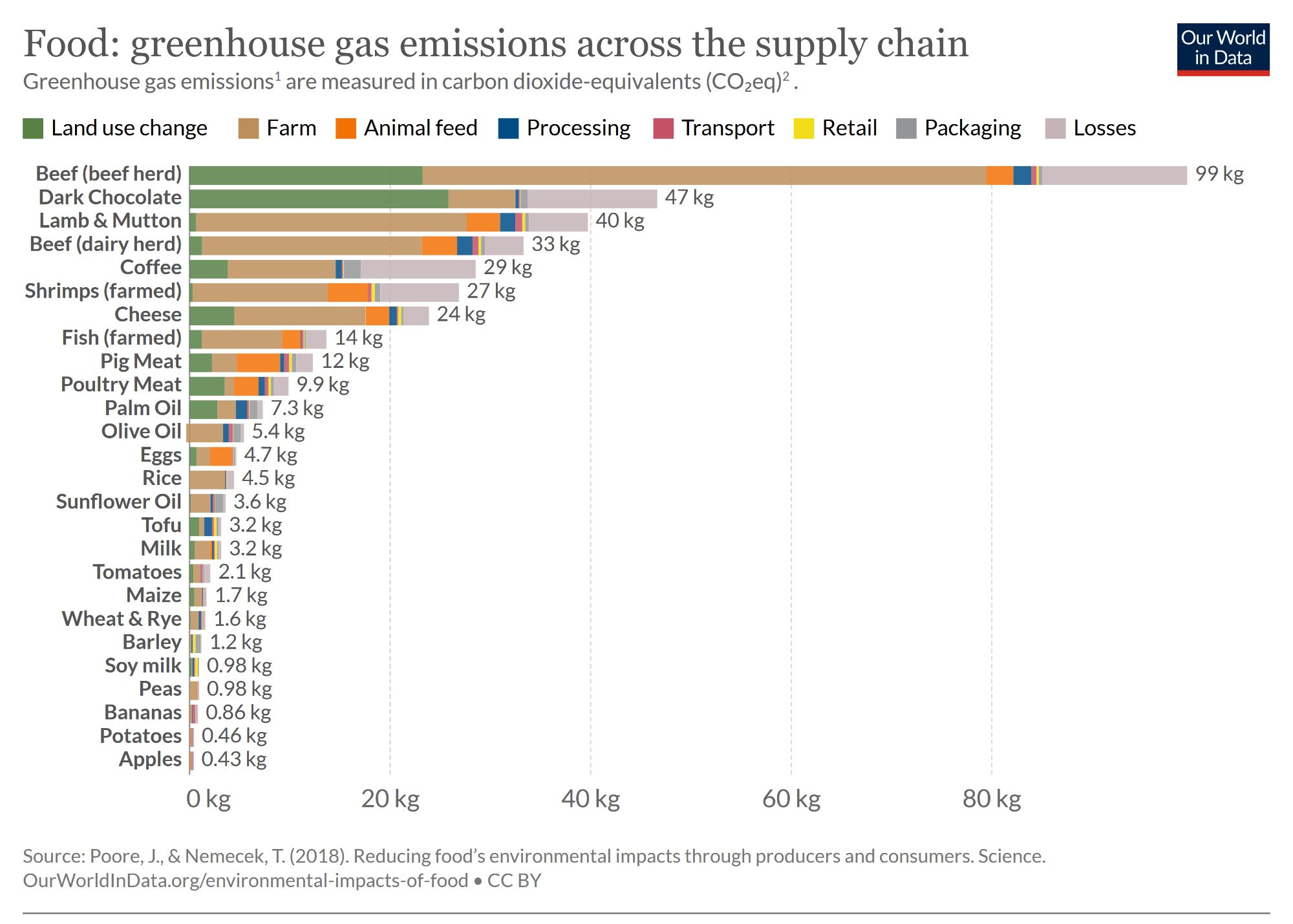

Greenhouse gas emissions from the supply chain of producing meat are generally larger than those from producing plant-based foods. How much larger? As much as 10 to 50 times.

Consider eating less meat. It’s unlikely to cost you any additional time to cook vegetarian or vegan meals instead.

Greenhouse gas emissions per kilogram of food product. Image from Our World in Data, CC-BY 4.0 license

IMPACT: Dietary choices can have a large impact on greenhouse gas emissions. The average American’s annual meat consumption results in 1.1 metric tons of CO2eq emissions (for an explanation of CO2eq, see here). [2] For a household of four meat eaters, the carbon emissions from eating meat are equivalent to over half of an average American home’s energy use for one year! (To make this calculation, see the U.S. EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator).

BONUS: If you, like most of us in America, buy meat from a supermarket, it’s likely that the meat came from animals in a factory farming situation, which can cause terrible suffering for our non-human relatives. By eating less of this meat you are contributing less to this suffering, and maybe sending a message through your power as a consumer.

4. Small and/or frequent household energy-conservation actions

TIME: less than 1 minute per action

When kids leave lights on all over the house, parents have been known to say “do you think our electric bill is too low?” Good question. Why leave lights on in a room where they’re not needed? And why not switch to LED light bulbs, which last for years, are highly energy-efficient, and have come down in price over 90% in the last fifteen years? Why wash clothes in hot water if they’re not that dirty, and modern detergents work really well in cold water?

Small, energy-saving actions take up very little time, and they will save you money as well as reducing your carbon emissions, so it pays to get in the habit of doing them.

Some have argued that each of these small, individual actions don’t amount to much, and we should focus our efforts instead on making large-scale, systemic changes to our energy, transportation, and agricultural systems. Is it too easy to greenwash ourselves if we take small actions, and feel content that we’ve done our part? It’s possible, and it’s important to remember that we need to support systemic change. But small actions do add up if enough people take them. And they are a starting point for many people. Helping children to learn energy-saving habits can be a great way to instill an environmentally-conscious mindset.

IMPACT: Switching 5 light bulbs in your home from incandescent to LED will avoid 288 pounds of carbon dioxide emissions. (To make this calculation, see the U.S. EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator).

A typical gas water heater might use 0.4105 therms/day. [3] Assuming 25% of this goes toward hot water for washing clothes, this leads to 438 pounds of carbon dioxide emissions per year. Washing in cold water will avoid these emissions.

BONUS: if you turn off outdoor lights at night, you’ll help insects such as moths, which are in dire need of protection. Recent studies have shown that artificial light at night can kill and exhaust flying insects, and disrupt reproduction and larval development in moths.[4,5]

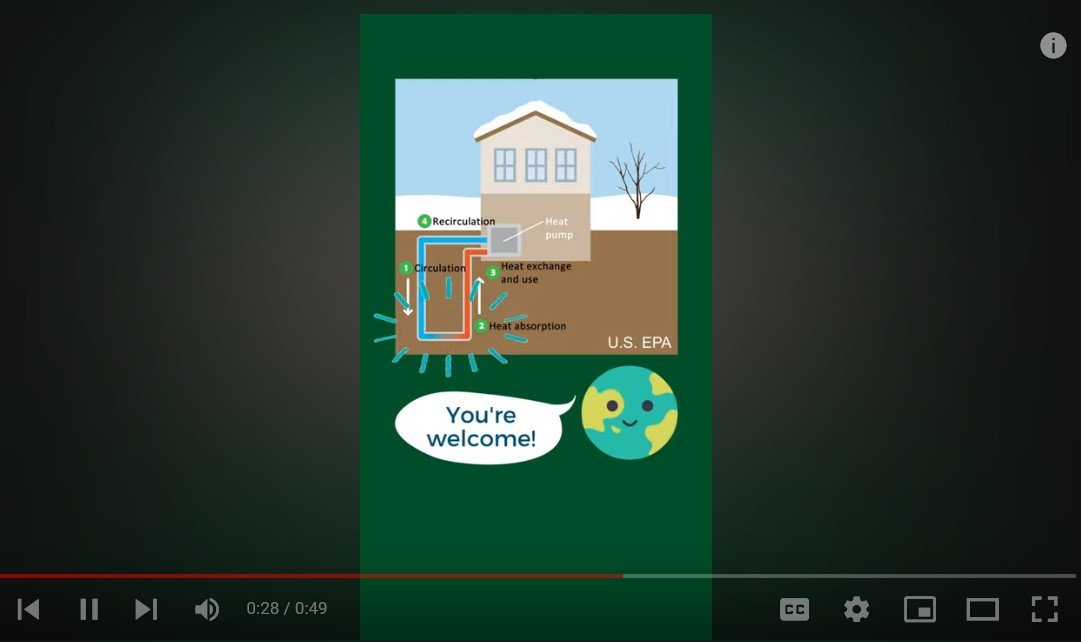

5. Choose renewable electricity

TIME: 1 hour per year

Many states allow you to choose your electricity supplier, and many suppliers offers “green” options. Take about an hour to research the choices in your region, and choose a supplier that generates electricity from renewable sources like solar, wind, and hydropower. You might be able to sign up for community solar, where you buy into or subscribe to a local solar farm.

Your local utility or local cooperative extension office can likely provide you with information about your choice of electricity suppliers (called Energy Service Companies or ESCOs) and options like community solar.

Learn more about buying renewable electricity from the U.S. Department of Energy.

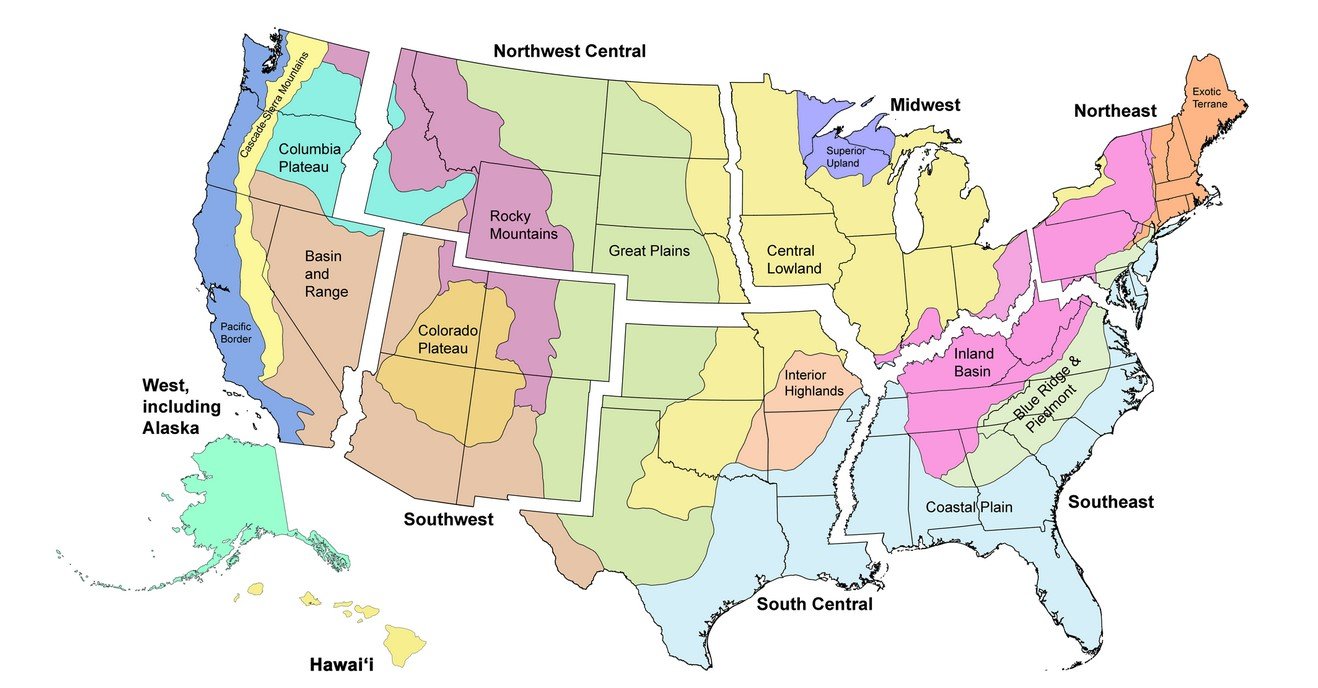

IMPACT: Electricity sources can have a large impact on greenhouse gas emissions. The impact of switching to renewable electricity depends on how electricity is generated where you live. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) maintains an energy database called eGRID that divides the U.S. into different regions. In upstate New York (EPA eGRID region NYUP), carbon dioxide emissions occur at a rate of 233.5 pounds/MWh of electricity. In much of Illinois and MIssouri (EPA eGRID region SRMW), the rate is 1,480.7 pounds/MWh. The average annual electricity consumption for a U.S. home in 2021 was 10.6 MWh [6] Given these numbers, on average a home in upstate New York could reduce its annual emissions from electricity by 2,475 pounds (1.1 metric tons) by switching to renewable electricity, and a home in the Illinois/Missouri region could reduce its annual emissions by 15,695 pounds (7.1 metric tons)! (To make these calculations of emissions vs. energy use, see the U.S. EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator).

6. Don’t waste your food

TIME: 5 minutes per day

Between 30% to 40% of food produced in the U.S. for consumption is wasted. [7]

This statistic is shocking on moral grounds when you think of all the people who are hungry. And food waste is also a climate issue. The production, transport, processing, packaging, and sale of food all use energy that produces greenhouse gas emissions, and if that food is wasted then all those emissions are for nothing. Additionally, when unused food is sent to a landfill instead of composted, decomposition in landfills releases methane—a powerful greenhouse gas—into the atmosphere. In 2020, 17% of all U.S. methane emissions came from landfills. [8]

Food waste is a systemic problem, but our individual actions matter. A study in 2020 found that in the U.S., “the average household wastes 31.9% of the food it buys.” [9]

Avoiding food waste doesn’t take a lot of time. You can spend a few minutes planning and checking what food you already have on hand before grocery shopping. Buy only what you need, and take only what you’ll eat on your plate. If you have leftovers, eat them during the next few days (saving time because you don’t have to cook) or freeze them. Learn how to store food properly so it doesn’t spoil.

Learn more about reducing food waste from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

IMPACT: If we cut 50% of our food loss and waste in the U.S., we would reduce greenhouse gas emissions by an amount equivalent to that from 23 coal-fired power plants. [10]

BONUS: It’s best not to discard food if you can avoid it, but if you do discard food, it’s better to compost it than to send it to a landfill. Composting doesn’t take much time—a few minutes here and there to take your food scraps out to your compost pile, and a few minutes to add leaves or grass clippings and occasionally turn the pile. You can use your compost to enrich your garden soil, and save time and money by not buying fertilizer or ready-made compost.

7. Talk about climate change

TIME: 5-20 minutes

Spend a few minutes talking about climate change solutions with friends, family, and colleagues. Post about climate change on social media. If you’ve taken some action, telling people about it might inspire others to act, too. Your voice has power.

Speak up on our “Share Your Views on the News” webpage in our online climate exhibit, Changing Climate: Our Future, Our Choice.

IMPACT: This might the most important thing you do. Societies can change through small-scale changes in social norms, and if it becomes normal for people to talk about climate change and show they care, it can strongly influence political and businesses leaders who have the power to make big decisions.

BONUS: You might have some interesting conversations! That could take more of your time, but it’s worth it.

Learn more about climate change science and solutions with these resources:

References

T.J. Blasing and Dana Schroeder, Energy, Carbon-emission and Financial Savings from Thermostat Control, Oak Ridge National Laboratory ORNL/TM-2013/55 (2013). https://info.ornl.gov/sites/publications/files/Pub41328.pdf , accessed Nov. 10, 2022

Berkeley Cool Climate carbon footprint calculator, https://coolclimate.berkeley.edu/calculator , accessed Nov. 11, 2022.

U.S. Department of Energy, Estimating Costs and Efficiency of Storage, Demand, and Heat Pump Water Heaters , https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/estimating-costs-and-efficiency-storage-demand-and-heat-pump-water-heaters , accessed Nov. 10, 2022

Boyes, D. H., Evans, D. M., Fox, R., Parsons, M. S. & Pocock, M. J. O. Is light pollution driving moth population declines? A review of causal mechanisms across the life cycle. Insect Conservation and Diversity 14, 167–187 (2021).

Deichmann, J. L. et al. Reducing the blue spectrum of artificial light at night minimises insect attraction in a tropical lowland forest. Insect Conservation and Diversity 14, 247–259 (2021).

U.S. Energy Information Administration, How much electricity does an American home use?, Oct. 12, 2022. https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=97&t=3 , accessed Nov. 10, 2022.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food Waste FAQs, https://www.usda.gov/foodwaste/faqs , accessed Nov. 10, 2022.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Overview of Greenhouse Gases, https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/overview-greenhouse-gases#methane , accessed Nov. 10, 2022.

Yu, Y. & Jaenicke, E. C. Estimating Food Waste as Household Production Inefficiency. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 102, 525–547 (2020).

Kirsten Jaglo, Shannon Kenny, and Jenny Stephenson, From Farm to Kitchen: The Environmental Impacts of U.S. Food Waste, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Research and Development, EPA 600-R21 171, November, 2021 https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2021-11/from-farm-to-kitchen-the-environmental-impacts-of-u.s.-food-waste_508-tagged.pdf accessed Nov. 11, 2022