A tribute to Rob Ross’s 25 years at PRI

by Warren D. Allmon, Director

March 2022 marks 25 years since Rob Ross joined the staff at PRI.

Rob Ross grew up in Buffalo. He received his undergraduate degree from Case Western Reserve University, where he studied under paleoecologist Peter McCall. I first met him in 1984, when he arrived as a first-year PhD student at Harvard. We had offices next to each other, in the bowels of the invertebrate paleontology collections of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. We were both teaching assistants (Harvard called them “teaching fellows”) for the large lecture course “History of the Earth and Life”, or Science B-16, taught by our advisor, Stephen J. Gould. As was true for so many of our fellow students, Gould’s course taught us both how to teach and was an immensely formative experience. Both of us served stints as “Head TF” for the course.

The graduate students were put in charge of a seminar series called “Earth History and Paleobiology”, and we invited some of the biggest names in our field to come give talks, asking them to speak on the general theme of “causes of evolution”. At some point someone suggested that it would be “fun” to ask these very senior scientists to contribute chapters to a book, of which Rob and I somehow became the editors. Gould introduced us to Susan Abrams, then an editor at Sinauer Associates (and later at the University of Chicago Press), and she was a wonderful mentor to us on the project. It was an amazing experience to be in continuous contact with the leaders of the discipline but it did have its downside: one of the contributors submitted a paper that, while fascinating, was just not along the lines we had in mind. We debated for days what to do, and we ended up somehow getting up the guts to write a long and carefully worded letter rejecting the manuscript for the book. That author was Dolph Seilacher, arguably one of the most distinguished paleontologists in the world. We thought that might be the end of our careers, but Dolph apparently did not hold it against us. Causes of Evolution: A paleontological perspective was published in 1990 to positive reviews. It was the first of many collaborations to come.

Rob decided that his dissertation would focus on studying microfossils – especially ostracodes (tiny bivalved marine crustaceans) – from the southwest Pacific region. He traveled extensively, sampling dozens of islands, and eventually making it all the way around the world at least once. He brought back scores of boxes and bottles of white sand, which formed the basis of his thesis, and have followed him loyally wherever he has gone since. He met former Harvard PhD Tom Cronin, a paleontologist at the U.S. Geological Survey who had also worked extensively in the south Pacific and would become de facto co-advisor of his thesis. Rob spent the last two years of his PhD at the USGS in Reston, Virginia, working in Tom’s lab. (Tom is now a PRI Trustee.)

Rob and Cornell President Emeritus Frank Rhodes at Ithaca’s Darwin Bicentennial celebration in 2009.

Besides being an excellent paleontologist, Rob was also skilled in all things computer, although he was always modest about his abilities. In 1991, he moved to Germany, to start a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Kiel. The fellowship was focused on paleoclimate modeling using a supercomputer. Soon after his arrival. Rob sent me a postcard, in which he wrote with his trademark self-deprecation that he was “drinking a beer, looking out over a city, preparing to start working on a project I know nothing about in a language I don’t understand”. He did a lot of great science there, and also met an exchange student from Missouri, who he married in 1992. Rob and Brenda moved to Japan in 1993, where Rob started as a professor at Shizuoka University.

Although he learned and accomplished a great deal in Japan, after Rob and Brenda were eager to return to the U.S., and in 1997 he came to PRI as our Educational Technology Manager, becoming Director of Education in 1998.

PRI in the late 1990s was going fast in several directions. We were trying to move beyond our history as a small collection and scholarly publisher, especially in the area of Earth science education. The World Wide Web seemed to offer us opportunities to have impact far beyond central upstate New York. Rob’s technical proclivities and ability to do and learn almost anything served us well in these aspirations. We were also embarking on designing a public Museum. In 1996, we had received gifts of $2 million to kick off this effort, and shortly after Rob arrived we were searching for consultants and hiring our first Director of Exhibits.

The planning and construction of the Museum of the Earth was an all-absorbing effort over more than 5 years, which consumed both of us (and everyone else at PRI). Rob was a critical participant in the seemingly endless meetings with exhibit designers as we slogged through our vision for what a 21st century museum of paleontology should contain. Boiling the entire history of the Earth and its life into 8,000 square feet is nearly impossible, and I cannot conceive of having been able to go through this without him. The dramatic finale came when our entire exhibit staff resigned 6 months before opening. I immediately asked Rob if he would assume the lead in bringing the project to the finish line. He said “yes… after I check with Brenda”. The Museum of the Earth would not have been completed without his stepping in at this crucial moment.

Rob played a huge role in organizing the Hyde Park mastodon excavation in 2000, and for years afterward ran the “Mastodon matrix project” which sent bags of dried mud from PRI’s mastodon excavations to more than 50,000 people around world and solicited their involvement in extracting and identifying fossils from it. Rob and co-authors published a paper on the results in 2009.

Rob and I have often joked that we can frequently complete each other’s sentences. Whether that’s literally true or not, the experience that we shared in graduate school gave us a common conception of what paleontology is and the ability to figure out how to do what we said we wanted to do – which was to turn PRI into a major player in Earth science education. For the past 25 years he and I have been yin-and-yang and good cop/bad cop as we have envisioned and strategized and tried and failed together to build something of national significance. Rob has been the careful thinker to balance my impulsive impatience, the consensus builder to temper my get-it-done-now insistence. He has done the trench work to figure out which hare-brained ideas will work and which ones won’t. He has been the boiler of much of the spaghetti that we have thrown against the wall to see what sticks. We have both sometimes said that the reason we have succeeded is that we did not know what wasn’t possible. I like to think that what keeps us going is that we both think that paleontology is the central science, a union of the Earth and life sciences that can uniquely illuminate and stimulate people to learn about both science in general and the history of the planet and its life in particular.

Rob’s patient and methodical approach to problems led to one of PRI’s most important educational initiatives. Shortly after becoming Director of Education, he surveyed teachers to ask what they needed to improve their teaching of Earth science. Their number one answer was collections of identified specimens. Unfortunately, prior experience had taught me that this was prohibitively expensive. Their second response, however, was for authoritative information on local geology, which is not usually available in textbooks produced for a national audience. Thus was born the Teacher-Friendly Guides to the Earth science of the U.S. Seed funding from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations got us started, and in 2000 we published the TFG for the northeastern region, to wide acclaim from teachers. Rob then began an exhausting effort to convince the National Science Foundation to support creation of TFGs for the rest of the country, and in 2007 PRI received a grant of $1.8 million to do just that. The result was a seven-volume set, completed in 2016 (and now being converted to online format in PRI’s new Earth@Home platform: https://earthathome.org/. The TFG grant revolutionized education at PRI (and, when the Great Recession came in 2008, helped the Institution stay solvent). It established PRI as a significant national provider of quality Earth science education materials.

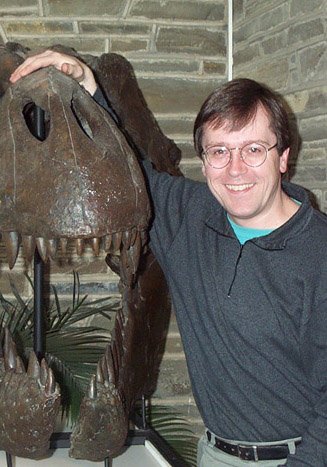

Rob at Taughannock Falls near Ithaca. He is a tireless educator in field and classroom, and has played a central role in everything PRI has done in public education over the past quarter century.

Rob’s second great educational accomplishment at PRI was “virtual fieldwork experiences” (VFEs). Although widespread on the web today, these online fieldtrips were novel in the early days of the web in the late 1990s. Rob saw that they were the future and has persistently pursued opportunities to make them essential tools for teachers. The result is a large and growing library of these resources online: https://earthathome.org/vfe/

Rob’s background in paleoclimatology was crucial as PRI pivoted in the early twenty-first century to educational projects focused on climate change, which is now one of the Institution’s major foci. Today a “climate team” of four staff work on the increasingly urgent issues of helping teachers teach about what is clearly the existential issue of our time. Under Rob’s leadership, PRI has become a major player in this critical area.

In 2007, local funders approached PRI and asked that we consider merging with the nearby Cayuga Nature Center. I remember vividly sitting in my dining room and asking Rob what he thought of the idea. He did not hesitate: “let’s do it”, he said. This response was, I think, born from both his wide conception of what PRI was about – a natural history museum for our region – and his complete commitment to our institutional success. He and I together composed the “case statement” for the merger and a strategy for making it happen. Although the implementation has not been without its obstacles (including funding and staffing issues), we both continue to believe that it was the right decision, and we think that will eventually be borne out.

Rob helps identify fossils for a group of students at the Museum of the Earth.

In the midst of all of this, Rob has also taught an extraordinarily popular course called “History of the Earth and Life”, first at Ithaca College and since 2018 at Cornell. He leads the annual James Potorti Gorge Hikes every August in local state parks. He writes an endless stream of proposals to keep his Education Department funded. He served as Acting Director of PRI during my sabbatical leave in 2007. He does whatever the Institution asks of him.

PRI’s many accomplishments over the past 25 years would have been impossible without the extraordinary loyalty, dedication, enthusiasm, creativity, intelligence, and staggeringly hard work of Rob Ross. And he has not only made a difference at PRI; he has made an enormous difference in Earth science education in the United States.

Thank you, Rob, for all you have done.