Darwin, Pollination, and Evolutionary Contrivances

First posted February 12, 2020

Charles Darwin was born on February 12, 1809. This date has come to be known as “Darwin Day,” marked around the world by celebrations of his life, work, and ideas. Since 2006, we have celebrated Darwin Day in Ithaca, New York with events at the Paleontological Research Institution (PRI), Cornell University, and elsewhere in the area. This year, we chose as our theme “The Power of Pollination,” in conjunction with the special exhibit “Bees! Diversity, Evolution, Conservation” at PRI’s Museum of the Earth.

Most people know that pollination is essential for the reproduction of many plants, including almost all of those that humans depend on for food and other essential needs. And many people know that insects are responsible for much of that pollination. But fewer probably realize the critical role that flowers and pollination have played in both the evolutionary process and in the history of evolutionary thought.

Darwin’s close friend and supporter, the famous botanist Sir Joseph Hooker (1817-1911), is said to have remarked that before Darwin, botanists thought that flowers existed “in order to beautify the landscape." Or they were called upon to illuminate other topics. For example, in his 1693 book A Natural History, English writer and member of Parliament Sir Thomas Pope Blount (1649-1697) wrote that “Every flower of the field, every fiber of a plant, every particle of an insect, carries with it the impress of its Maker, and can – if duly considered – read us lectures of ethics or divinity.” Such ideas were in the tradition of Natural Theology, which Darwin knew well from his reading as a student at Cambridge in the 1820s, which said that species are as we see them for some divine purpose. Even a decade after publication of The Origin of Species in 1859, Tennyson wrote in his poem “Flower in the Crannied Wall”:

“… Little flower – but if I could understand

What you are, root and all, and all in all,

I should know what God and man is.”

Darwin’s work exploded these notions, at least among naturalists. Darwin said that the form of organisms serves no higher or final purpose. Species have the characteristics they do solely because evolution has shaped them over time to survive and reproduce. Their features are therefore a mixture of adaptations to their local environments shaped by natural selection, and unchanged inheritances from their ancestors. Centuries of speculation about divine design and teleology, at least with respect to material nature, were dispensed with.

Pink lady’s slipper orchids (Cypripedium acaule) blooming in a forest in central New York, May 2019. This species is pollinated by bees. Photograph by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Flowers played a major part in this intellectual change. In the years after 1859, Darwin published ten other books, each of which provided additional evidence for the hypotheses he had laid out in The Origin (which he referred to as an “abstract” because it did not cite previous published work as the customs of science even then required). The first of these volumes was about flowers and was titled On the Various Contrivances by which British and Foreign Orchids are Fertilised by Insects, and on the Good Effects of Intercrossing and was first published in 1862 (a second edition appeared in 1877 with a slightly abbreviated title). As evolutionary biologist Michael Ghiselin writes in a foreword to a 1984 reprint, this book

“evoked a major revolution in botany and in biology as a whole. It completely changed our conception of sexuality and gave rise to an enormous literature on pollination ecology. Everything that has subsequently been done on the broad topic of coevolution and related areas has been influenced, directly or indirectly, by this book.” (Ghiselin, 1984, p. xi)

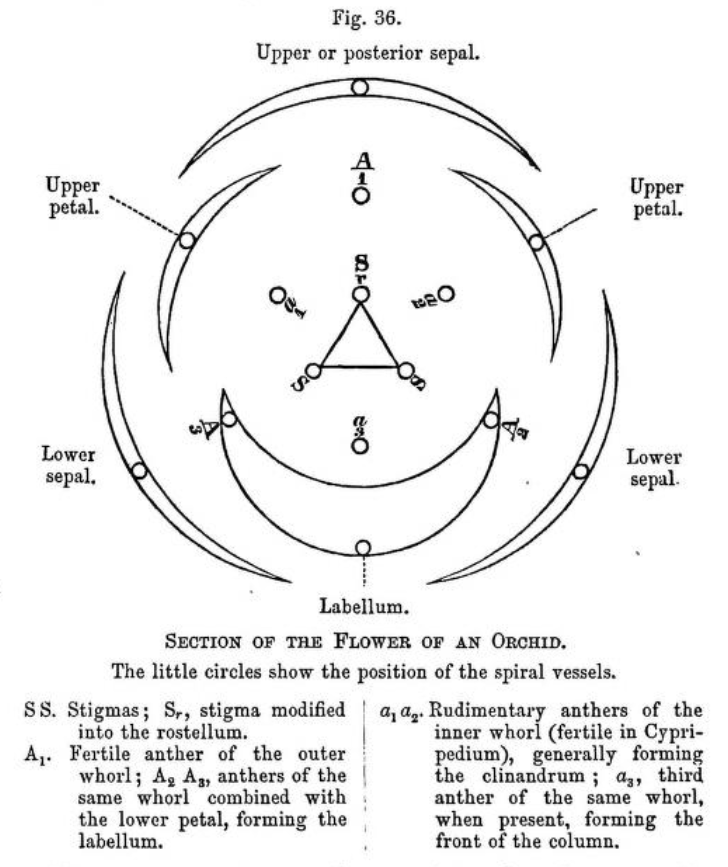

Darwin’s schematic diagram showing a section through a typical flower and the basic parts of all flowers. (Fig. 36 from Darwin, 1862, 1877.)

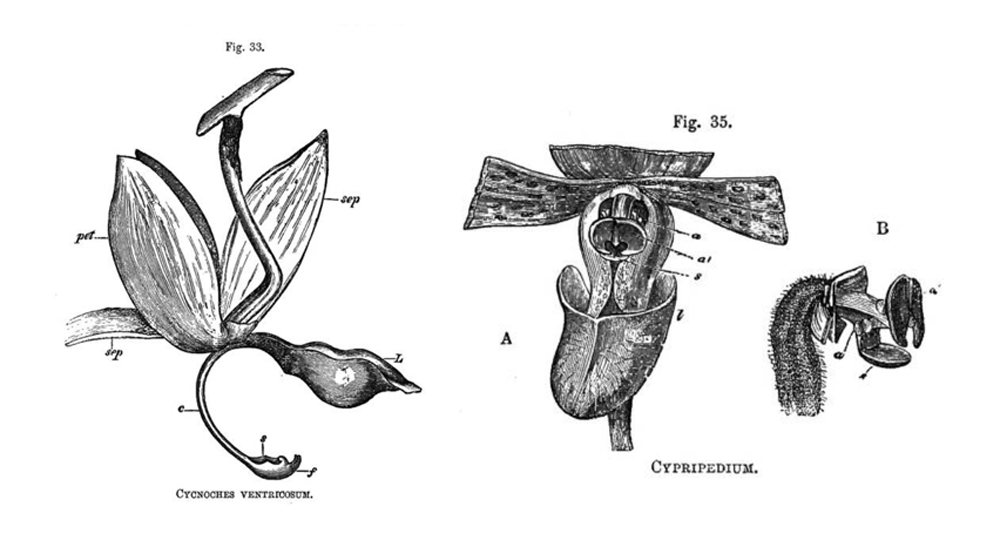

Darwin’s orchid book tried to explain why living orchids look as they do—especially why they come in such a bewildering array of forms, and are so different from most other flowers. To accomplish this, he had to explain the origin of apparently “new” organs or structures. Darwin suggested that such feature were in fact not new, but modifications of pre-existing features. Most of these modifications, he argued, were elaborate “contrivances” to facilitate pollination. In evolving from other flowering plants, orchids had changed various parts of their flowers to attract, entice, trick, and otherwise lure insects to move pollen from one flower to another. Even though orchids looked incredibly different from most other flowers, they were really just versions of a common theme—highly modified variations that nevertheless reflected a “unity of type,” and a common evolutionary ancestor.

In making this argument, Darwin not only laid out a theory for the history and causes of the evolution of orchids, he beautifully explicated one of the most powerful categories of evidence that evolutionary change (he called it “descent with modification”) had actually occurred at all. Darwin’s argument was that a close examination of flowers showed that there were many features in common to all of them. When detailed comparisons of these features were made between different kinds of flowers, it appeared that the dissimilarities were not those of kind but of degree, and that there were patterns of these similarities and differences that were not “intelligible” without accepting that the species possessing them shared a common evolutionary ancestor from which they had diverged.

Darwin informally used the term “contrivances” for complicated structures made of multiple functioning parts. His use was primarily descriptive, but but has subsequently taken on the connotation of a structure made through modification of existing anatomical parts:

“Orchids exhibit an almost endless diversity of beautiful adaptations. When this or that part has been spoken of as contrived for some special purpose, it must not be supposed that it was originally always formed for this sole purpose. The regular course of events seems to be, that a part which originally served for one purpose, by slow changes becomes adapted for widely different purposes.” (1862, p. 346)

Darwin referred to these similarities-with-differences as homologies, a term invented by his contemporary Richard Owen, who did not accept evolution. While Owen viewed the patterns as the result of variations on an undefined “archetype,” Darwin viewed them as evidence of evolutionary change, descent with modification.

He wrote in Orchids:

Two illustrations of orchids from Darwin’s Orchid volume (figs. 33, 35; 1862, 1877), showing how very different flower shapes are actually comprised of the same basic set of parts.

“The importance of the science of Homology rests on its giving us the key-note of the possible amount of difference in plan within any group; it allows us to class under proper heads the most diversified organs; it shows us the gradations which would otherwise have been overlooked, and thus aids us in classification…The naturalist, thus guided, sees that all homologous parts or organs, however much they may be diversified, are modifications of one and the same ancestral organ; in tracing existing gradations he gains a clue in tracing, as far as that is possible, the probable course of modification through which beings have passed during a long line of generations.” (1877, p. 233)

The naturalist will, Darwin continued,

“see how curiously a flower may be moulded out of many separate organs, — how perfect the cohesion of primordially distinct parts may become, — how organs may be used for purposes widely different from their proper uses, — how other organs may be entirely suppressed, or leave mere useless emblems of their former existence. Finally, he will see how enormous has been the amount of change which these flowers have undergone from their parental or typical form.” (1877, p. 234)

In the Origin Darwin wrote that, of all the categories of evidence, it was this kind of information from “comparative anatomy” that provided the most convincing and abundant evidence for evolution. That is, patterns of similarities among species can be explained best by inheritance from a common ancestor. Such observations, wrote Darwin,

“seem to me to proclaim so plainly, that the innumerable species, genera, and families of organic beings, with which this world is peopled, have all descended, each within its own class or group, from common parents, and have all been modified in the course of descent, that I should without hesitation adopt this view, even if it were unsupported by other facts or arguments” (1859, pp. 457–458).

The anatomical similarities Darwin was talking about are specifically those that seem to have no apparent function or adaptive value, or to have functions very different from those they were apparently originally built to perform. It was one of Darwin’s central insights that such similarities are best explained by descent with modification, as opposed to some form of supernatural creation. In other words, only in an evolutionary context do such features “make sense.”

Despite this widespread sense among evolutionists that evolutionary remnants observed in homologies provide powerful evidence for descent with modification, homology itself is in many ways a difficult concept to comprehend, much less to see as compelling evidence for evolution, especially for those such as students who lack extensive biological knowledge. It is counterintuitive that Darwin argued that it is lack of change that is the best evidence that change has occurred, and there are at least three other reasons that homology is challenging:

The full range of functions of a given trait is frequently not evident to non-specialists, let alone whether that trait is being selected for in the local environment or whether it is persisting due to ancestry and/or constraint. For example, it may not be obvious whether having six legs is or is not the “best” possible functional solution for all insects. If one assumes a priori that all creatures are “perfectly” or “optimally” adapted—an idea stemming not only from special creation, but also from widespread and frequently extreme adaptationism within modern evolutionary biology, as well as being embedded in popular culture and implied in the narrative of much of today’s public natural history media and education—then there is no reason to read history into morphology. (Thus, by this reasoning, for example, one would assume that, because all insects have six legs, it must therefore be the case that it is optimal for every insect species to have six legs.)

Use of the present static condition of something to infer how it changed in the past is an unfamiliar way of thinking to many people and counter to their common experience. The evidence of change with which most people are most comfortable is direct observation. Fixed features labeled as “homologies” may therefore be difficult to accept as evidence of evolutionary change, because they do not convey the impression that anything is actually happening, or—by extension—has happened. This is a widespread problem with all evolutionary science, which largely uses static data as evidence of a dynamic process, and is likely one explanation for the common objection from creationists that we cannot “see evolution happen.”

Homology can be a tricky concept, because it risks forming a circular argument in which structures are considered homologous because of common origin, and these animals are said to have a common origin because they have homologous structures. An independent assessment of ancestry and origins is therefore needed. Thus, it is important to help students recognize that diverse independent evidence gives us confidence that descent with modification has occurred and that comparative anatomy is an effective tool to find evidence of common ancestry in organisms around us.

Darwin’s key insight about such features was that if organisms have a history of change—of descent with modification—then that history will inevitably leave traces or remnants. These can be recognized, Darwin suggested, in features that do not appear well-suited to their present function or to have any function at all. “Organs or parts in this strange condition,” he wrote, “bearing the stamp of inutility, are extremely common throughout nature” (1859, p. 450). The existence of such structures, “organs in a rudimentary, imperfect, and useless condition, or quite aborted, far from presenting a strange difficulty, as they assuredly do on the ordinary doctrine of creation, might even have been anticipated, and can be accounted for by the laws of inheritance” (1859, p. 456). Crucially, Darwin then extended this insight:

“On this same view of descent with modification, all the great facts in Morphology become intelligible, — whether we look to the same pattern displayed in the homologous organs, to whatever purpose applied, of the different species of a class; or to the homologous parts constructed on the same pattern in each individual animal and plant” (1859, p. 457).

The most compelling argument for interpreting homologous similarities as evidence of evolution is that they are the inevitable traces of historical change. These traces demonstrate that the process by which living things have come to look as they do necessarily results in their possessing features that indicate the pattern of their historical genealogical relationships. Evidence of evolution is not rare, or especially difficult to find or see; on the contrary, by its very nature, evolution leaves an abundant and—once you know what you’re looking for—conspicuous evidentiary record which can be seen in the flowers in our own backyards.

References and Further Reading

Allmon, W. D., and R. M. Ross. 2017. Evolutionary remnants as widely accessible evidence for evolution: The structure of the argument for application to evolution education. Evolution: Education and Outreach, 11:1.

Boulter, M. 2008. Darwin’s garden. Down House and The Origin of Species. Constable, London, 251 pp.

Darwin, C. 1859. On the origin of species. John Murray, London, 502 pp.

Darwin, C. 1862. The various contrivances by which orchids are fertilised by insects, and on the good effects of intercrossing. John Murray, London, 300 pp.

Darwin, C. 1877. The various contrivances by which orchids are fertilised by insects. 2nd ed. John Murray, London, 300 pp. (Facsimile reprint, 1984, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.)

Dean, S. A. 2009. Charles Darwin. After the Origin. Paleontological Research Institution and Cornell University Library, Ithaca, NY, 156 pp.

Edens-Meier, R., and P. Bernhardt (eds.). 2014. Darwin's orchids: Then and now. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 384 pp.

Ghiselin, M. T. 1984. Foreword. In The various contrivances by which orchids are fertilised by insects. 2nd ed., by Charles Darwin. Facsimile reprint, 1984, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. xi-xix.

Yoon, C. K. 2000. In love with orchids, their inspiration and excess. The New York Times, January 25. Link.