Reinventing the Educational System in a Time of Disruption

Note: This post is an outgrowth of Reinventing the Educational System in a Time of Disruption: The Kick-off event for Science in the Virtual Pub, an online event held March 26, 2020. This link will take you to the announcement for the event. A video of the event is here and presentation slides are here. This post is not a transcription of the session, but draws ideas from the same pool and complements it. The conversation has continued every other Thursday since April 9, 2020 at 7:30 pm EDT. To join these ongoing discussions, register here. To see upcoming events for Science in the Virtual Pub, click here.

Suddenly, we have set aside the centuries-old operating system of the educational system and need to create a new operating system on the fly. While this is very stressful and connected to a tragedy of epic and as yet uncertain proportions, it's also incredibly exciting. We have the opportunity (and responsibility) to make something new. It has the potential to repurpose the incredible human resources we have in the teaching force across the entire system, and to unshackle those of us who have felt constrained by the tyranny of the course, the calendar, and the clock.

The talk that this post draws from had these goals:

make the case for why educational reform is so needed and why it has been so difficult;

share relevant insights from other sectors of society;

build understandings of educational systems by comparing them to ecosystems with special attention to disturbance ecology; and,

set us to the task of changing the world.

This post makes a start on those goals, but attention to the second goal here is minimal, and it will receive more attention in a future post.

Before tackling any of those goals, though, it’s important to note that it’s profoundly unlikely that what someone looking back on the spring of 2020 will remember is the difference between mitosis and meiosis or how to factor a polynomial. It may be something about the humanity, or lack thereof, of their teachers, employers, friends, or families. Sadly, for many of us it will be remembering those we lost and those who suffered greatly during these very hard times that are really only just beginning. As we move forward now, we’d do well to think about how we’ll want to be remembered for acting in these times.

Educational innovations have failed to have noticeable positive effects at scale

Educational reform efforts of the last several decades have failed to improve the outcomes of schooling in ways detectable in the general population. I believe this is largely because they’ve failed to really reform very much. The scale, of course, has changed. At virtually every level, we have a larger segment of the population participating in formal education than ever, but the structure is strikingly similar to what it has been for much more than a century.

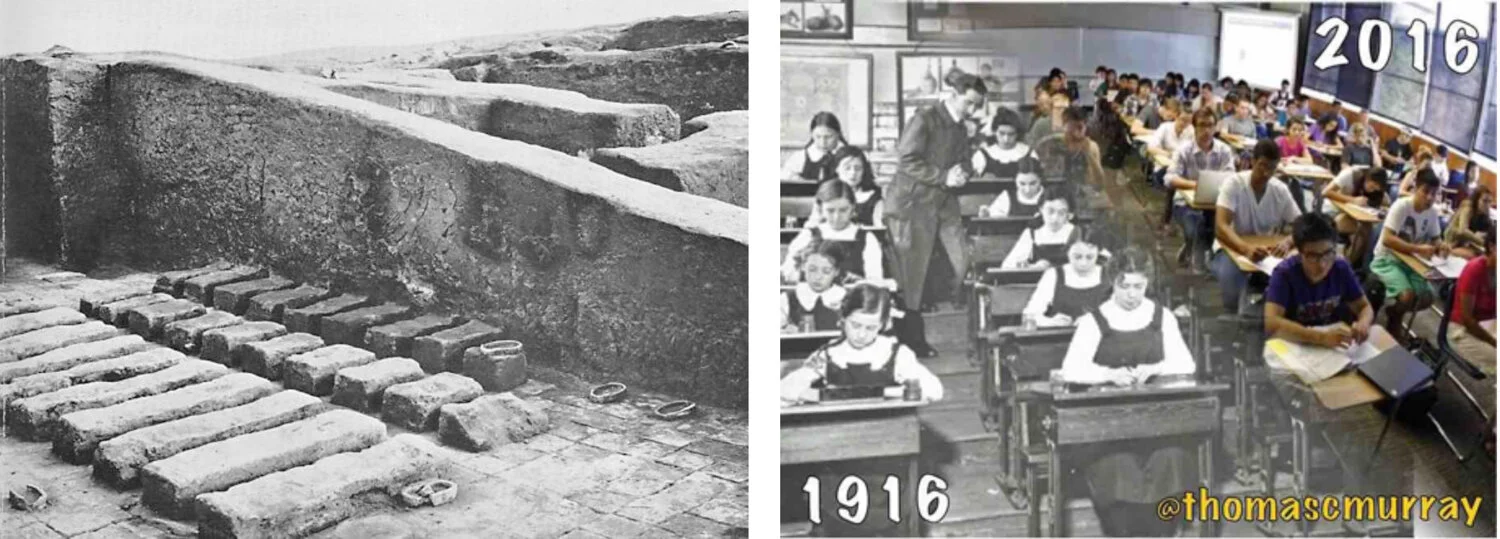

Classrooms of 2020 look strikingly like those of centuries and millennia ago. Perhaps a 4,000 year old design has limited educational power. Suddenly, this structure has been abandoned. Left: A Sumerian classroom from ca. 2000 B.C.E. (from Cole, 2005). Right: Images of classrooms from 1916 and 2016 mesh seamlessly (from Murray, 2016).

I pose a pair of challenges: first, identify a way the average American is a more capable reasoner than the average American of 40 years ago. If you are able to do that, the second challenge is to tie that improvement to an innovation in K-16 schooling.

It is simple to identify ways in which user outcomes have improved dramatically in a range of societal systems—communications, entertainment, transportation, energy, finance, and commerce to name several—but extraordinarily difficult to do so for formal educational systems. It should go without saying that I am not speaking about test scores, but things noticeable in the day-to-day functioning of society. In each of those other listed sectors of society, it is easy to rattle off innovations of recent decades most of us would not want to give up. I’ve now asked some version of these questions of thousands of educators and scientists. Only one response (so far) has withstood any kind of scrutiny, and it’s not really the domain of a traditional school discipline.

I do think there may be one aspect of society that is better and it is at least partly traceable to changes in schooling: at least up until very recently, bullying has been less tolerated, and people have generally become more accepting of difference. That’s important and should be both celebrated and investigated for transferable lessons.

Why can’t we identify improvements in the educational system more broadly that have made us wiser or more knowledgeable? There are several reasons (and they probably aren’t what you think). We do know more about effective learning and teaching, but struggle to put that into practice in a broad and coordinated way. It is, of course, true that great things are happening—and have long happened—in many classrooms scattered geographically and across the grade span. But they tend to be in isolated pockets, greatly limiting their effectiveness. The greatest obstacles are likely not technical, but cognitive and cultural. We tend to keep doing what we’ve always done because of cognitive biases and cultural paradigms. Consider the following:

Imagine that you know nothing about school, but do have some idea about how you have come to understand important ideas. Imagine that someone says,

“Hey! I’ve got a great idea! Let’s put 2,000 teenagers into a building, sort them into groups of 20 or 30, have someone talk at them about the Battle of Hastings for 45 minutes, then have them move down the hall and have someone else talk at them for exactly the same amount of time about rocks (or whatever)! And, let’s do this over and over and over again, day after day after day, and year after year, for years on end! Isn’t that a great idea?”

No. This is, indeed, a bad idea, yet it is what we do. The structure of schooling is not simply mismatched with research on how people learn, it is generally at odds with this body of research. Why is this approach, then, so commonplace? There was no educational equivalent of Charles Darwin who derived a set of natural laws of education and laid them out in On the Origin of Courses (see Duggan-Haas, 2014). The approach suits certain needs fairly well and other needs well enough, but the fundamental structure of schooling is completely uninformed by research on how people learn. Of course it is. The structure of schooling was well established before how people learn was carefully studied.

Standards efforts, like the Next Generation Science Standards and the Common Core State Standards Initiative, offer fantastic visions of what students might learn. But they are akin to rewriting users' manuals while believing that it's creating new operating systems for education. The operating system is both embodied in the physical architecture of schooling shown in the images above and in the temporal architecture of schooling from scales of minutes to decades (in 1999, David Orr referred to this as “the architecture of crystallized pedagogy”). The structure of systems is fundamental to determining the outcomes of systems. Given this, we should be more surprised by changes in outcomes than by their stasis.

Put another way, the infrastructure of schooling in buildings, technologies, and the arrangement of classrooms is the hardware of schooling. The schedules and the one-to-many model of content delivery—along with the content delivered by various types of media—are the software. We’ve rewritten the operating manuals thinking it will change the hardware and software. Many of us don’t even read operating manuals.

Mixing metaphors: on operating systems, ecosystems, and edusystems

The operating system of schooling has suddenly been set aside. The metaphor of educational systems as operating systems is one helpful way to consider the changes and the stasis we’ve seen in recent decades. Outside forces have crashed the system and we’re rebooting. Another useful metaphor is seeing educational systems as ecosystems. And, it’s worth noting that if we don’t understand how one thing is like and not like something else—if we don’t understand things metaphorically—we don’t understand them in any meaningful way.

The novel coronavirus is a disturbance to the ecosystems of education (what I will hence refer to as “edusystems”) that none of us have seen in our lifetimes, and an opportunity of epic scale. We can and should learn lessons from how disturbances change ecosystems to inform our work as we move forward in these uncertain times.

Seeing educational systems as ecosystems provides a raft of insights about how the systems operate and how we might influence their evolution. (A fair amount has been written about seeing educational systems as ecosystems for many years. Recently, attention has been given to “STEM ecosystems.” This latter scholarship is less nuanced and more naive in its conceptions of ecosystems, suggesting, for example, how to create new ecosystems as if there are blank slates for learning ecosystems somewhere. Discussion of this literature in depth goes beyond the scope of this post. I hope to visit this literature in future posts.) Two interrelated aspects are the importance of initial conditions and first cover. Both of these are also connected to understandings of ecological niches. “Initial conditions” refers to the status of the individual agents and the environment at the beginning of some process. “First cover” refers to the practices, species or agents that take root first after disturbance.

Again, the structure of schooling was established before there was substantial research on how people learn. Those structures, the age-graded school, the course, the classroom, the system of grading as percentages or on a scale from A to F, the schedule across all those scales from minutes to decades, are all part of the first cover of edusystems.

Disturbance in an ecosystem (by fire, for example) can reset initial conditions. After an area is denuded the first species to take root will often dominate the landscape (for a time) regardless of measures of efficiency of the species in the niche. Sometimes, in other words, it is not survival of the fittest, but rather survival of something that more or less fits but was there first. This is not meant to imply that competition is unimportant, but rather that species that move into a system first have strong competitive advantages over whatever may come along later.

In ecosystems and edusystems, competition plays out on multiple scales in both time and space. When change in a system is inhibited, this does not imply the absence of competition, rather it is an aspect of competition: “… no species necessarily has a competitive superiority over another. Whichever colonizes the site first holds it against all comers” (Connell and Slatyer, 1977, p. 1138). A competitive advantage that comes from taking control first is hardly unique to ecosystems or educational systems. Gaining initial control is an advantage in ecosystems, edusystems, battlefields and basketball. But it doesn’t mean the game is over in any of those situations.

That moving in first is why I did the online session sort of on the fly, an initial condition I would like to help set is the consideration of what we do tomorrow and next week may have implications for years or decades to come. This blog post is also in that spirit, though it draws from decades of thinking along these lines. My dissertation was titled Scientists are from Mars, Educators are from Venus: Relationships in the Ecosystem of Science Teacher Preparation and was completed 20 years ago.

I don't claim to have durable solutions, but I want to plant the idea that the changes we make now should be made with an eye to long-term changes in the educational system. I am fearful we’re in the process of resetting the initial conditions poorly, and that the first cover that sets in will hold even if it’s not very good.

A great many institutions and individuals are rushing to fill newly vacant niches in these highly disturbed systems. We might do well to consider what characteristics, beyond getting there first, are associated with durability in rebooted systems. That’s a topic for another post (or maybe a few posts), though these issues were touched upon in the session. Relevant concepts from ecosystems to inform this line of thinking—which I intend to visit when we continue the discussion on April 9—include invasive species and how their characteristics and the characteristics of the system they invade influence changes in systems, as well as ecosystem engineer species (like beavers, for example) that reshape the infrastructure of ecosystems.

Setting the task of changing the world

The big goal is really to take advantage of this disturbance in the ecosystem, or setting aside of the educational operating systems, to make something better that lasts beyond the current crisis. That involves moving from doing what we know how to do to doing what needs to be done, as educational researcher Michael Fullan noted. It’s a heavy lift.

These are days we will remember for the rest of our lives. Let’s get them right. It’d be nice if we had a little time to think about what comes next in educational systems to avoid setting in place structures and procedures as problematic as what they’re replacing. We need a pause. Some states may be doing that. Michigan is considering ending the school year early, while New York is not only pushing ahead, but also cancelling spring break, all while no one really knows what they’re doing. There are good arguments for both approaches, and clearly no easy answers here.

We probably won’t get a pause. Let’s do our best to move thoughtfully.

As noted at the outset, this is a companion to the kick-off session of Science in the Virtual Pub. There’s a recording of that session as well as presentation “slides” (actually a Prezi). The discussion of these issues continue alternating Thursdays at 7:30 pm EDT. You can register for those discussions here and join our ReinventED - Disrupted Google Group here.

See what’s coming up at Science in the Virtual Pub here.