PRI's Historical Collection of Teaching Models

by Maria Altier

Last updated August 28, 2020

Have you ever wondered what you don’t see at the Museum of the Earth? What we keep locked up behind the scenes? Besides our research collection that contains over 7 million fossils, there are a few other collections beyond those in our public exhibits that may surprise you. One of these is our small collection of teaching models. Part of our mission is to mix art and science, and these items ride that line. Many of them are also antiques, early relics of the history of museums and science education in the United States. In the absence of a rare or fragile original specimen, casts—direct copies made from a mold of that original—can be used to teach. If the original specimen is organic, or just too big or small to be practical, you might show your students a model—an original, but accurate to life sculpture, often at a larger or smaller scale. Both casts and models populate the museum today, so next time you visit, keep an eye out!

Henry Ward (left) and Buffalo Bill Cody (right). Image from RocWiki.

Many of the antique casts and models that we keep off exhibit come from the Ward's Natural Science Establishment, an early provider of material to America’s first large museums. Ward’s still exists today as Ward’s Science, providing teachers everything from preserved animal specimens, to lab supplies, to its original offering: rock, mineral, and fossil specimens. The story of Ward’s Science (and our models) begins more than 150 years ago, not too far away from where the Museum of the Earth sits today.

The company’s founder and namesake, Henry August Ward, was born in upstate New York in 1834. He received a somewhat eclectic education in his youth, bouncing from institution to institution, before briefly living in Europe from 1854 to 1860. There he traveled across the continent, gathering geological specimens, meeting other collectors, and collecting casts of famous European fossils. He found himself enchanted by the large museums of Europe and began dreaming of American institutions to rival them.

On his return home, Henry Ward briefly became a Professor of Natural Sciences at the University of Rochester, his chief qualification apparently being the vast number of specimens that he could offer. Ward wasted no time in setting up a mineralogical museum at U of R to showcase his best finds. Behind the scenes he still had hundreds of specimens, just waiting to be traded away to other collectors like him—and trade he did, traveling as often as possible to collect more specimens to fuel his growing business. As time went on, Ward became less and less focused on displaying his own collection as a museum and more on the collecting, and then the trading, storing, and shipping of that collection.

P.T. Barnham’s circus elephant, Jumbo, which was taxidermied by Ward’s Natural Science (Wikimedia Commons; public domain).

Though he was perpetually struggling financially—his collecting trips were not cheap—Ward’s star as a provider of specimens rose. He expanded beyond geology and into biology with mounted animals and skeletons, as well as racist depictions of humans, including the 1888 series titled “Masks of Faces of Races of Men.” The name “Ward” became recognized beyond a professor with a passion for collecting and turned into a brand known across America. His customers ranged from local college presidents, including Cornell’s Andrew D. White, to the famous P.T. Barnum, who’s deceased circus animals were taxidermied by Ward for a museum at Tuft’s university. Ward’s taxidermy and casts did exactly as he had hoped: they kicked off a new era of large public natural history museums in America that highlighted examples of life’s present and past biodiversity.

In 1906, Henry Ward became the first automobile fatality in Buffalo, NY. He was laid to rest in Rochester’s Mount Hope Cemetery beneath a beautiful erratic boulder flecked with bright red jasper. More exactly, he was mostly buried there: his brain resides in Cornell’s Wilder Brain Collection.

Now that you know the history, let’s get to the fun part: the art! You might want to know what the models we have look like. Let’s explore the PRI Model Archives. Some of the Ward models in our archives are shown in the photograph below.

Let’s zoom in on one a little. This is one of the rectangular, block-shaped models you see in the first picture and it depicts an ancient crustacean called Eryon propinquus (now called Cycleryon propinquus), originally found in Eichstätt, Bavaria, Germany. The fossil itself does not have much relief, so would not stand out well as an artificial cast. Therefore, it was painted in naturalistic shades of brown and finished with a glossy varnish to stand out against the matte tan background “rock.” Sometime during its long life, one of the corners of the model broke off, but was glued back on (many of the models are damaged as a result of age and use).

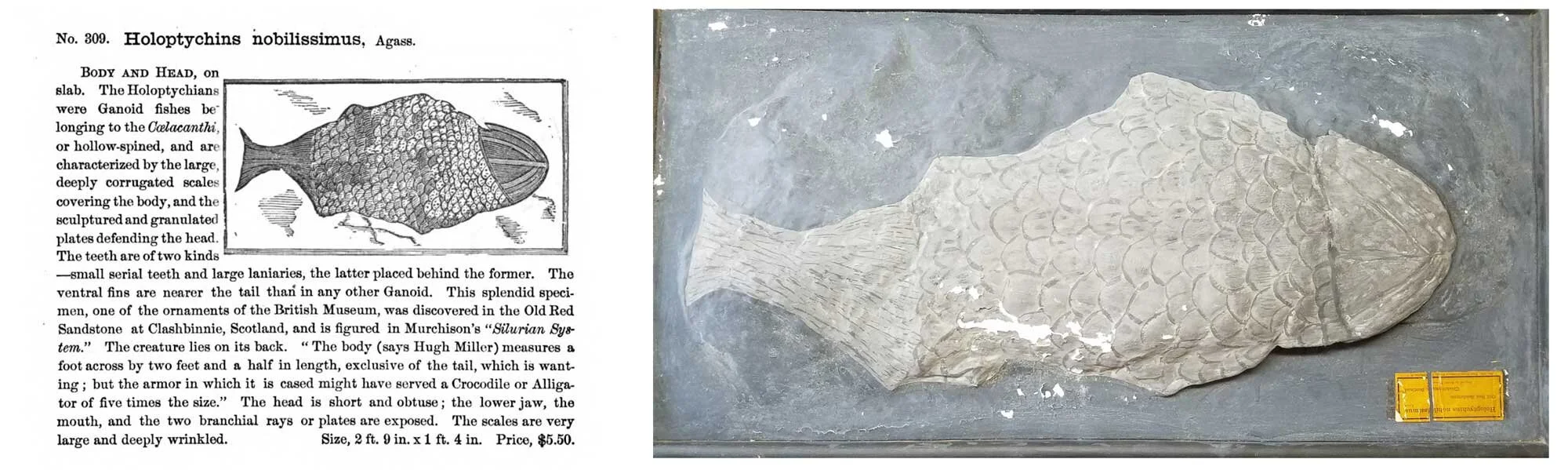

As a demonstration of a fossil in a museum, this is exactly the kind of thing you want. It tells the story of the world when it was alive. In context with other fossils, it can create a tapestry of life as it was millions of years ago. Still, this is not the kind of thing that could support actual research, or even careful study in a classroom. Looking closer, you can see that the lines are a little clumsy. The head is a fluffy-looking forest of brush strokes and the claws don’t have any sort of detail beyond being v-shaped. The model has a serial number on the back that can be used to find it in one of Ward’s old model catalogs. As you see, there are a few differences and it clearly lacks the detail of an actual fossil of this species.

As advertised. At least the price is reasonable.

Real fossil of Cycleryon propinquus, from the Jurassic Solnhofen Limestone of Germany. Photograph by James St. John (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

This, however, is not necessarily a bad thing. These objects weren’t produced for careful study. Instead, they were made for display in museums. Henry Ward wanted to facilitate the rise of the American museum and educate people all over the United States in the burgeoning science of geology. Simplifying and clarifying fossils worked towards that goal. Much as some of these casts do not match their advertisements (and some of them do not match), they helped to introduce new audiences to the diversity of life recorded in the fossil record. Indeed, American museums would not be what we know them as today without Henry Ward.

My favorite ward model… the similarity is astounding.

References and Additional Resources

The Brains of Uris Hall. Ithacating in Cornell Heights Blog, Dec. 27, 2014. Link.

RocWiki: Henry August Ward. Link.

RocWiki: Ward’s Natural Science Establishment. Link.

Ward’s Science Store. Link.

Old Ward’s Science Catalogs. Link.

The Ward Project. Link.

Ward Biography, River Campus Libraries. Link.

The crustacean Cycleryon on Wikipedia. Link.