Darwin and Insects

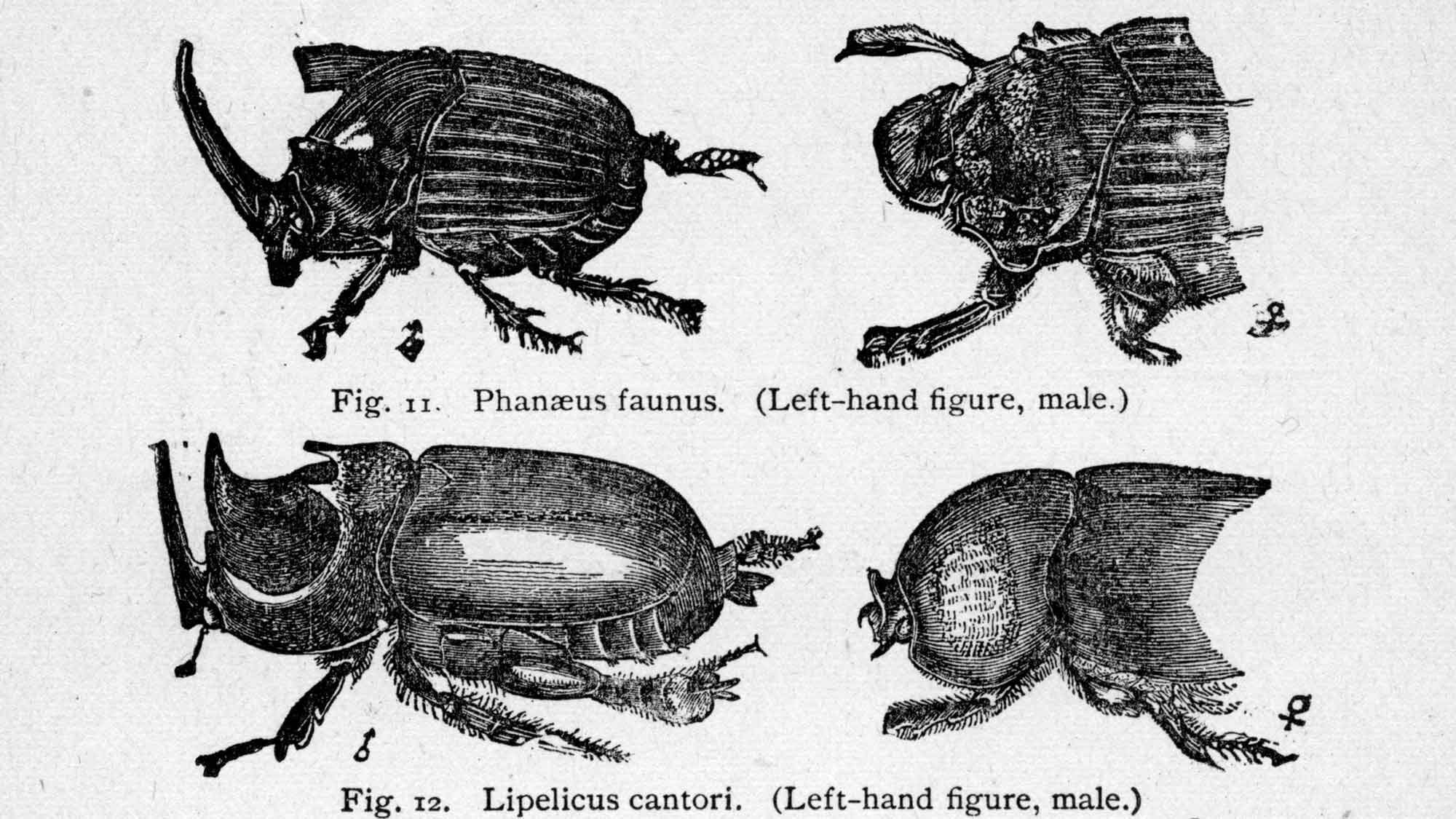

Illustrations of beetles from The Descent of Man (Darwin, 1871).

by Dr. Warren D. Allmon, Director, Paleontological Research Institution

Last updated: January 28, 2022

Charles Darwin is universally known as the founder of the modern science of evolution. It is far less widely appreciated how many other scientific fields he contributed to, or even founded. Indeed, the scope of his scientific work is astonishing. The only times he ever actually identified himself with a particular scientific field he referred to himself as a geologist, and it was primarily in geology that his most substantial early scientific interest and contributions lay, including books on the geology of South America, volcanic islands, and the formation of coral reefs.[1] Before writing On the Origin of Species, Darwin spent eight years studying the taxonomy of barnacles. After the Origin, he devoted much of his time to botany, and published six books on plants. The last of his books was on earthworms. He invented the scientific study of animal behavior, the concept of sexual selection, and the application of natural science to explaining the origin and characteristics of human beings. He was an ecologist, paleontologist, and anthropologist. Yet amidst all of this, he was also a passionate entomologist, and throughout his long life he remained fascinated with insects.

Darwin's interest in entomology began in childhood, and he credited his second cousin William Darwin Fox (1805–1880) for introducing him to the subject. As a college student, Darwin was well known for his obsessive insect collecting. Fellow students at the University of Cambridge remembered that beetle catching was one of his main interests (although it may not at the time have been mainly for scientific reasons). As he wrote in his Autobiography:

“…no pursuit at Cambridge was followed with nearly so much eagerness or gave me so much pleasure as collecting beetles. It was the mere passion for collecting; for I did not dissect them, and rarely compared their external characters with published descriptions, but got them named anyhow. I will give a proof of my zeal: one day, on tearing off some old bark, I saw two rare beetles, and seized one in each hand; then I saw a third and new kind, which I could not bear to lose, so that I popped the one which I held in my right hand into my mouth. Alas! it ejected some intensely acrid fluid, which burnt my tongue so that I was forced to spit the beetle out, which was lost, as was the third one.”[2]

Charles Darwin as a young man. Portrait by George Richmond, ca. late 1830s (public domain).

Despite his amateur status, a number of Darwin’s college observations were cited in the standard work at the time on British insects, Illustrations of British Entomology by James Francis Stephens (1827–1845). Stephens attributed the records to “C. Darwin Esq.”, and they might be said to constitute Darwin's first publication.

On his voyage around the world on HMS Beagle, Darwin collected just about everything he could, including many insects. These collections are now mostly in the Natural History Museum at the University of Oxford, along with a set of detailed entomological notes made during the trip. Some of the insect specimens that Darwin collected may be viewed here. In his Journal of Researches into the Geology and Natural History of the Various Countries Visited by H.M.S. Beagle (usually known as simply Voyage of the Beagle), first published in 1839, Darwin commented on numerous aspects of the insects he had encountered, including bird parasites being transported to other localities, insects found in bird stomachs, noise-producing butterflies, army ants, wasps stinging and storing spiders for food, locust swarms, ant lions, and flipping click beetles.

In the Origin (1859), Darwin mentions insects about 50 times, including observations of the resemblance between the larval stages of moths, flies and beetles; the origin of blind insects in caves; the constancy of structure of antennae in hymenoptera (bees and wasps); that certain flies lay a large number of eggs; bugs (hemipterans) that look like moths; and why worker ants are sterile. He discussed how cell-making behavior in bees may have arisen, noting the gradation of nest-making ability from the simple nests of bumble bees through intermediate types to the very complex combs of honeybees. In a passage both perceptive and charming, he noted how complex ecological interactions affected insect abundance:

“The number of humble [i.e., bumble] -bees in any district depends on the number of field-mice, which destroy their combs and nests… Now the number of mice is largely dependent, as every one knows, on the number of cats… Hence it is quite credible that the presence of a feline animal in large numbers in a district might determine, through the intervention first of mice and then of bees, the frequency of certain flowers in that district!”[3]

Darwin was particularly interested in flightless beetles on islands. He noted, for example, that on the Portuguese island of Madeira 200 of the 500 known species of beetles are flightless. Darwin argued that:

“the wingless condition of so many Madeira beetles is mainly due to the action of natural selection… For during thousands of successive generations each individual beetle which flew least, either from its wings having been ever so little less perfectly developed … will have had the best chance of surviving from not being blown into the sea; and on the other hand, those beetles which most readily took to flight will oftenest have been blown to sea and thus have been destroyed.”[4]

Darwin’s “wind hypothesis” has recently been tested on the extremely windy islands of the Southern Ocean (around Antarctica). Researchers examined every idea proposed to account for flight loss in insects, and none explain the high proportion of flightlessness (almost 50%) on these islands as well as Darwin’s.[5]

In his book Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871), Darwin discussed insects in several different contexts. There are seven pages devoted to sex ratios in insects, and an extensive discussion, with illustrations, on why some beetles have horns on their heads (Darwin argued it was because of male-male competition for females). In his book Insectivorous Plants (1875), Darwin explored the types, sizes, and numbers of insects captured by various plants, and considered why different-sized insect species could escape from particular plants.

One of Darwin’s most striking entomological achievements was a prediction. After publishing the Origin, Darwin became fascinated with orchids and argued that many of the complex structures of their flowers were the result of natural selection for pollination by particular species of insects. One orchid species he examined, Angraecum sesquipedale from Madagascar, had a nectary one foot long. Darwin predicted in his 1862 book On the Various Contrivances by which British and Foreign Orchids are Fertilised by Insects that there must exist a species of moth or butterfly with a proboscis long enough to reach the nectar at the bottom of this structure. No such species was then known. In 1867 Alfred Russel Wallace (co-discover with Darwin of the theory of natural selection) published an article in which he supported Darwin's hypothesis, remarking that the African sphinx moth Xanthopan morganii (then known as Macrosila morganii) had a proboscis almost long enough to reach the bottom of the orchid’s nectary. Wallace wrote “That such a moth exists in Madagascar may be safely predicted; and naturalists who visit that island should search for it with as much confidence as astronomers searched for the planet Neptune,-- and they will be equally successful!”[6] Exactly such a species was eventually discovered in Madagascar and described in 1903: the moth Xanthopan morgani praedicta has a wingspan of about 15 cm (6 inches) and a proboscis about 30 cm (12 inches) long, and was named in honor of Wallace’s and Darwin’s predictions.[7]

The sphinx moth Xanthopan morganii. Image by “Esculapio” (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license).

A 1961 review of Darwin’s contributions to the study of insects suggested that “Probably Darwin’s greatest contemporary contribution to the field of entomology was his encouragement of individuals working in the subject.” The authors write that through his theories, Darwin “stimulated further experimentation and observation through questions” and in print and private correspondence “was unstinting in his praise and appreciation of the work of others.” For example, in a letter to the tropical naturalist Henry Walter Bates (1825–1892), Darwin described Bates’ 1862 paper “Contributions to an Insect Fauna of the Amazon Valley,” in which the evolution of mimicry in butterflies was carefully described, as “one of the most remarkable and admirable papers I have ever read in my life.”[8]

An ichneumon wasp preparing to lay its eggs on a host caterpillar. Photograph by “AnemoneProjectors” (Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license).

Insects played another important role in Darwin’s thinking. Prior to Darwin’s theory of natural selection, the leading explanation for the fit of organisms to their way of life was divine creation. The school of thought known as “natural theology” held that the beautiful adaptations of species to their environment were evidence of the wisdom and benevolence of the creator. (This is the same argument that is used today by advocates for the version of creationism known as “Intelligent Design.”) A major problem for this view is the existence of apparent suffering and cruelty in nature. One of the main examples of this for early naturalists were wasps known as ichneumons.

Ichneumons are an extraordinarily diverse group of parasitic wasps (there are at least 25,000 described species, which may be only a quarter of their true diversity). Female ichneumons lay their eggs on or in a living host, usually an insect or spider. When the larvae hatch, they begin to feed on the host, frequently eating it in such a way as to allow it to remain alive for as long as possible, permitting the larvae to complete their development. The host is literally eaten alive.

How could such a horrific phenomenon be the product of a benevolent God? Early nineteenth century advocates of natural theology – such as William Kirby (1759–1850), at the time Britain’s foremost entomologist (and an Anglican clergyman) – had a variety of responses, including emphasizing the intricacy and efficiency of the parasite. Carnivores in general, they suggested, are actually a net good, decreasing suffering and increasing (as one of them wrote) “the aggregate of animal enjoyment” in the natural world, since death eliminates the injured and the sick and keeps populations of prey balanced with their food supply. The apparent cruelty of the slow deaths of ichneumon hosts, however, seemed a particular challenge to such explanations.

Darwin himself was deeply troubled by the question. In 1860 he wrote in a famous letter to American botanist Asa Gray:

“I own that I cannot see as plainly as others do, and as I should wish to do, evidence of design and beneficence on all sides of us. There seems to me too much misery in the world. I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent and omnipotent God would have designedly created the Ichneumonidae with the express intention of their feeding within the living bodies of Caterpillars, or that a cat should play with mice.”[9]

As eloquently noted by the late Stephen J. Gould (in my personal favorite among his 300 essays for Natural History magazine), Darwin solved this vexing issue by saying that there is no solution. Nature is not cruel or evil, and does not exist to offer us moral lessons; it just exists. The adaptations of species are not parables for anything; they are contingent results of evolution by natural selection. In that same letter to Asa Gray, as Gould put it, Darwin wrote, “in words that express both the modesty of this splendid man and the compatibility, through lack of contact, between science and true religion”[10]:

“I feel most deeply that the whole subject is too profound for the human intellect. A dog might as well speculate on the mind of Newton. Let each man hope and believe what he can.”

Learn more about our events in celebration of Charles Darwin.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Corrie Moreau for comments on previous drafts.

References and further reading

Bates, H.W., 1862, Contributions to an insect fauna of the Amazon Valley. Transactions of the Linnean Society, 23: 495–566.

Darwin, C., 1859, On the origin of species. John Murray, London, 502 p.

Gould, S.J., 1982, Nonmoral nature. Natural History, 91(2): 19-26. (Reprinted in: Hen’s teeth and horse’s toes [1983]. W.W. Norton, New York, pp. 32–45.)

Herbert S. 2005. Charles Darwin, geologist. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 508 p.

Klopfstein, S., B.F. Santos, M.R. Shaw, M. Alvarado, A.M.R. Bennett, D. Dal Pos, M. Giannotta, A.F. Herrera Florez, D. Karlsson, A.I. Khalaim, A.R. Lima, I. Mikó, I.E. Sääksjärvi, S. Shimizu, T. Spasojevic, S. van Noort, L. Vilhelmsen, and G. Broad, 2019, Darwin wasps: A new name heralds renewed efforts to unravel the evolutionary history of Ichneumonidae. Entomological Communications, 1: ec01006.

Kritsky, G., 1991, Darwin's Madagascan hawk moth prediction. American Entomologist, 37(4): 206-210.

Leihy, R.I., and S.L. Chown, 2020, Wind plays a major but not exclusive role in the prevalence of insect flight loss on remote islands. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 287(1940), p. 20202121.

Minet, J.P., P. Basquin, J. Haxaire, D.C. Lees, and R. Rougerie, 2021, A new taxonomic status for Darwin’s “predicted” pollinator: Xanthopan praedicta stat. nov. (Lepidoptera Sphingidae Sphinginae). Antenor, 8 (1): 69-86.

Porter, D.M., 1985, The Beagle collector and his collections. In The Darwinian heritage. D. Kohn ed., Princeton University Pres, Princeton, NJ, p. 973–1019.

Remington, J.E., and C.L. Remington, 1961, Darwin's contributions to entomology. Annual Review of Entomology, 6: 1-12.

Rothschild, W., and K. Jordan, 1903, A revision of the lepidopterous family Sphingidae. Novitates Zoologicae, 9: 1-972.

Smith, K.G.V., 1987, Darwin's insects: Charles Darwin's entomological notes, with an introduction and comments by Kenneth G. V. Smith. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Historical Series 14, No. 1: 1-143.

Wallace, A.R., 1867, Creation by law. Quarterly Journal of Science, 4: 471-488.

Footnotes

[1] In his unpublished autobiographical essay of August 1838, Darwin described himself as ‘I a geologist,’ and in an entry in his ‘E’ notebook in 1839 as ‘myself a geologist’ (Herbert 2005, pp. 2, 328). In what is apparently his only published identification of himself as a geologist (Porter 1985, p. 984), the reference is more indirect.

[2] Barlow, N., ed., 1958, The autobiography of Charles Darwin 1809-1882. With the original omissions restored. Edited and with appendix and notes by his grand-daughter Nora Barlow. Collins, London, p. 62. See here.

[3] Darwin (1859: 74).

[4] Darwin (1859: 136).

[5] Leihy and Chown (2020).

[6] Wallace (1867: 477). This article was reprinted in Wallace’s 1891 book Natural Selection and Tropical Nature.

[7] Rothschild and Jordan (1903). See discussion in Kritsky (1991). The moth has recently been elevated from a subspecies to a separate species, Xanthopan praedicta (Minet et al., 2021; see here).

[8] Remington and Remington (1961)

[9] Darwin to Asa Gray, May 22, 1860. This quotation has been the subject of much commentary, including calling ichneumons “Darwin’s classic monster” and “the wasp that made Darwin doubt God.” A group of ichneumon specialists has recently proposed calling ichneumons “Darwin wasps,” “to reflect the pivotal role they played in convincing Charles Darwin that not all of creation could have been created by a benevolent god” (Klopfstein et al., 2019), and this seems to have caught on among entomologists generally, e.g., see here.

[10] Gould (1982).