What Did Darwin Do?

A short summary of the broader impact of Darwinism

Left: Marble statue of Charles Darwin on display at the Natural History Museum, London. Right: Title page of On the Origin of Species.

by Dr. Warren D. Allmon, Director, Paleontological Research Institution

Last updated: February 1, 2022

Editor’s note: This essay is adapted and expanded from: Allmon, W.D., 2009, Afterword: What did Darwin do? In S.A. Dean, Charles Darwin: After the Origin. Paleontological Research Institution Special Publication No. 34. Cornell University Library and The Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, NY, pp. 135-140.

“Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.” (Dobzhansky, 1973)

“… what makes the Darwinian revolution so exceptionally important is what there is outside of biology that also fails to make sense except in the light of evolution.” (Stamos, 2003: p. 2)

Whatever one thinks of Charles Darwin and the ideas he expounded, there is an almost universal recognition that few individuals in history have had so much impact on humanity’s view of itself, its world, and its place in that world. And yet there is a profound paradox in this recognition.

Ever since publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859, it has been clear that an intellectual genie had been released from its bottle, and that humans would never again be able to see the world in quite the same way as they had before. This recognition started even in Darwin’s lifetime, and was signified by his burial in Westminster Abbey in 1882 amidst England’s greatest heroes. It continued over the following century with Darwin’s routine inclusion in virtually every list of the most influential thinkers in history, and the Origin’s in virtually every list of the most important and influential books ever written. Darwin’s name appears on scores of imposing public buildings in many countries, alongside those of Aristotle, Plato, Newton, and Einstein. The words “evolution” and “natural selection” are ubiquitous in literature, advertising, common speech, and popular culture. Darwinian evolution is widely viewed by scientists as one of the central ideas in all of science, and it is simply taken for granted by most researchers and teachers in most scientific fields.

Thus, for more than a century, the world (at least the Western world) has been in large part a Darwinian world: we all live within a worldview that is thoroughly imbued – scientifically and culturally – with ideas first laid out convincingly by Charles Darwin in 1859. Yet we are so embedded in this reality that we usually do not generally recognize it; as writer Gillian Beer has put it, “We pay Darwin the homage of our assumptions”[1].

The paradox lies in the fact that the majority of the people in the world, and in the United States, neither understand nor accept these ideas. This incomprehension and rejection is remarkable. It seems similar to patients choosing to stay away from doctors because they don’t accept that blood really circulates in veins and arteries, or that bacteria and viruses don’t really cause disease; or people choosing not to use electric lights because they don’t accept that electricity is real. How can ideas wholly accepted by essentially every knowledgeable scientist be so roundly rejected by a majority of non-scientists? Why, more than 200 years after Darwin’s birth and more than 150 years after the publication of his most important work, do we hold such mutually exclusive conceptions of this man and his ideas?

There are many possible explanations for this situation.[2] Just one of them might be that many people in fact do not realize the reach and influence of Darwin. Did Darwin really fundamentally change our views, or just massively mislead us? Did he muddy the waters of understanding ourselves and our place in the world, or bring the clarity we had been seeking for so long? What, in other words, did Darwin do? If we could have an adequate understanding of this, then perhaps at least one important obstacle to understanding and accepting his ideas could be overcome.

We should start any answer to this question with three simple historical facts. First, within 20 years of the publication of the Origin in 1859, essentially all Western scientists with any significant experience in biology or geology (as well as many other thinking people) had fully accepted that evolution or, as Darwin originally called it, “descent with modification,” is true. Although debates continued to rage – and still do among scientists today – about the mechanisms by which evolution occurs, by the time of Darwin’s death in 1882 there was (and still is) essentially no professional debate about whether evolution is the best scientific explanation ever proposed for observations about the nature of living things.

Examples of present and past organisms, all a shaped and related by the process of evolution. Image from the Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

Second, despite his success in convincing much of the world of the truth of evolution, Darwin’s attempts to persuade his readers and colleagues that his proposed particular mechanism for evolution, which he called natural selection, was the primary reason evolution occurred were an almost complete failure in his lifetime. It was not until the 1940s that biologists would come to widespread acceptance of natural selection.

Third, although he was not solely responsible for the late nineteenth century rise of biology as a successful separate branch of science, Darwin was unquestionably a crucial part of this ascent. Even though natural selection was not immediately embraced in detail, its form as an explanation and the style of its presentation made it suddenly clear that biology could be just as rigorously empirical and scientific as physics and chemistry. Natural selection was simple and plausible, and, most importantly, it was completely materialistic and non-teleological – it did not require supernatural intervention. And Darwin presented it with extraordinary attention to logic and empirical detail, a form of argument heretofore restricted to the physical sciences.

Thus within science, what Darwin did is clear: he very quickly convinced his fellow scientists that evolution was true, and laid the groundwork for the eventual acceptance of natural selection as its primary cause; by so doing, he made the scientific study of whole organisms possible. As philosophers Vittorio Hösle and Christian Illies put it: “It is hardly an exaggeration to state that Charles Darwin has shaped biology more significantly than anyone else before or since. His importance can be compared only with that of Aristotle…”.[3]

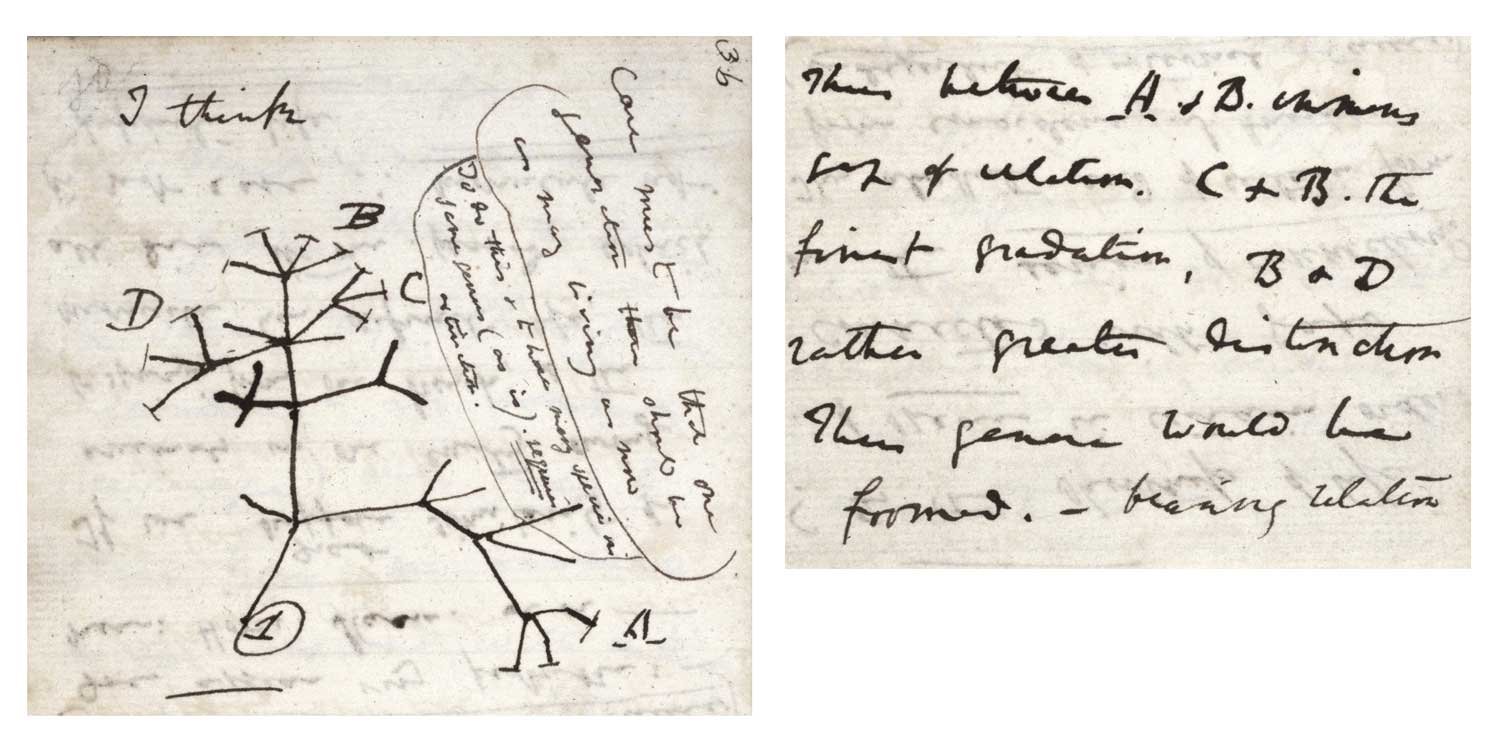

Darwin's famous 1837 notebook sketch of an evolutionary tree, labeled "I think." The interpreted handwriting associated with the sketch reads, "Case must be that one generation should have as many living as now. To do this and to have as many species in same genus (as is) requires extinction. Thus between A + B the immense gap of relation. C + B the finest gradation. B+D rather greater distinction. Thus genera would be formed. Bearing relation [next page begins] to ancient types with several extinct forms." Source: Wikipedia/Wikimedia Commons (public domain). Also see the Darwin Online webpage.

Outside of science, however, Darwin’s influence was and is perhaps even greater, although more complicated to understand.

Exploration of Darwin’s broader impact follows two broad lines of scholarship. One is the explication and documentation of the actual historical influences of his thinking on evolution and natural selection on fields such as literature, religion, philosophy, the social sciences, and general perceptions of history and humans’ place in nature. The other lies in the growing calls for new and more rigorous applications of natural selection to a wide variety of other areas, such as medicine, psychology, economics, linguistics, political science, and international relations. These two lines of investigation are not equivalent. The first addresses what has already happened, while the other argues for influences or applications that have only begun to affect thought and practice in major ways, or which may, in the future, be seen to have become important influences.

Historian Peter Morton described an attempt to “write a comprehensive account of the cultural impact of Darwinian biology” even just up to the beginning of the twentieth century as “reckless”.[4] Reckless or not, the task is close to impossible. For one thing, the literature on Darwin is vast. It is estimated that more than 7,500 books have been written about him, with more appearing each year.[5] Yet the magnitude of the topic is further evidence of the need to continually revisit and reassess it. This essay is only an attempt at a short summary and I have tried only to provide some entryways into the enormous literature on the topics I discuss.

Historical Influences

Darwin was clearly both a reflection and a cause of larger changes in society and culture. His “scientific arguments were,” as Rutgers English professor George Levine puts it, “part of a whole movement of which Darwin can be taken as the most powerful codifier”.[6] We can clearly recognize and group the influence of these arguments under at least six headings.

1. The rise of science

Whether we like it or not, the dominance of science (and its technological offspring) is one of the central defining features of modern life – and not just for scientists, but for everyone else as well. Darwin was both follower and leader of the currents that created this situation. Today, when we largely take for granted – or at least consider the strong possibility – that most subjects can be treated by the methods of science, it is perhaps difficult to imagine a time or a world view in which this was not so. Darwin obviously did not single-handedly put science in the central role it plays today, but, as Levine puts it, Darwin “can be taken as the figure through whom the full implications of the developing authority of scientific thought began to be felt by modern nonscientific culture.”[7]

2. Human nature and our place in nature

In the midst of the rapid advance of science and technology that marked Darwin’s time, human beings were largely exempt. Medicine was (very slowly) becoming more mechanistic and scientific, but virtually every other aspect of humans was off-limits to science. Darwin changed this forever, and made humans a legitimate scientific subject. He proposed the first serious scientific theory that explained the origin, history, and nature of humans – what was at the time often referred to as “man’s place in nature,” and he laid out the techniques by which these topics could be studied empirically. Although the first edition of the Origin had only a single mention of humans (“Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history,” p. 488), it was clear to virtually every reader what the larger implications of Darwinian evolution were for humans. Not everyone agreed with these implications, of course, but Darwin made them acceptable topics of serious scientific discussion.

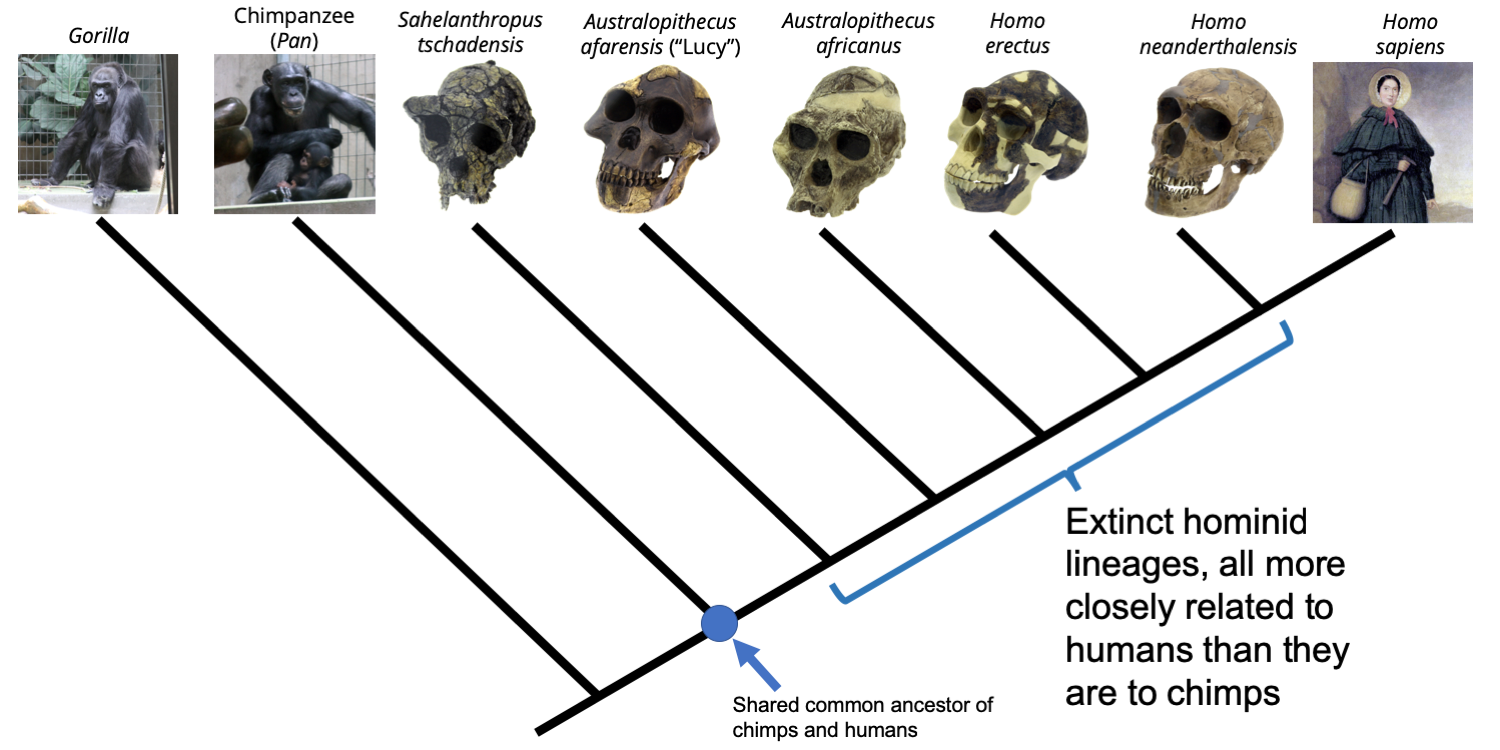

Phylogenetic tree depicting the relationships between gorillas, chimpanzees, humans (depicted by 19th century paleontologist Mary Anning; portrait public domain), and human-like relatives. Image from the Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

Darwin’s influence marks the beginning of much of what today are called the social sciences, including psychology, sociology, and economics. We take for granted that these fields can address issues of human thought and behavior from an objective, observational, and secular (i.e., “scientific”) point of view. This is not all Darwin’s doing. Others before him had considered what we would now call “social evolution” of various sorts. But the creation of these modern fields of inquiry would not have happened without him. “The authority of science,” writes Levine, “and its extension from natural phenomena to human was both a condition of Darwin’s enterprise, and its consequence.”[8]

3. Religion

Although it is true that many religious people, from 1860 to the present, have argued vehemently that evolution and/or Darwinian natural selection are utterly irreconcilable with belief in any meaningful God or adherence to any traditional religious faith, this is not by any means true for all religious people or traditions. Despite suggestions to the contrary, Darwin obviously did not destroy religion. Indeed, persistent predictions about the imminent disappearance of religion have all proven utterly incorrect. It is also true, however, that, at least in most Western countries, organized religion today has less direct impact on the daily lives of people, governments, and institutions across the industrialized world than it did a century and a half ago. Although clearly not all of this change was caused by science in general, or Darwin in particular, both were clearly involved. As conservative as we now think Victorian culture was, the period was in fact a time of pervasive secularizing of nature and society and in the exploration of the consequences of that secularization.

4. Philosophy

Immediately after the Origin was published, many thinkers looked to evolution as a source of understanding on philosophical issues. Darwin’s view of evolution was non-progressive and non-teleological, and this challenged some core assumptions of nineteenth century thought. Darwinism contributed to the decline of idealism and romanticism, which were still widespread in mid-nineteenth philosophy in both Europe and America. Darwin’s idea of a continuous “struggle for life” implied that morals and values were not inherent or absolute, and that nothing could persist if it could not maintain itself in its environment. Darwin’s emphasis on empirical experience argued for a new approach to seeking continuity between humans and the natural world, which many previous philosophers had found only in the world of thought.

Not all philosophers responded enthusiastically[9], but the practicality of Darwin’s approach strongly affected the thought of a number of influential philosophers and thinkers, particularly in America, including especially William James, Charles Sanders Pierce, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and John Dewey. These “pragmatists” argued for the importance of ideas that were workable over those that were more ethereal and absolute. The entire field of ethics was essentially thrown open (a condition in which it largely remains). No longer was it self-evident that ethical standards could come only from revealed religion. After Darwin, writes Levine, “Value would now be seen to inhere not in permanence, but in change, not in mechanical design but in flexibility and randomness… Once the consonance between the natural and the intentional is lost, the space for willed constructions of meanings… opens up.”[10] Humans, in other words, must seek – and make – meaning for themselves as best they can.[11]

5. Literature

The nature of a culture’s fiction literature is frequently taken as one of the clearest windows into its core values, tastes, and assumptions. If this is true, then the impact of Darwin – as revealed in his influence on at least American and British literature – is great indeed. Just in the past quarter-century, literary scholars have produced detailed demonstrations of Darwinian influences on the writing of many authors, including Joseph Conrad, Charles Dickens, George Eliot, William Faulkner, Robert Frost, Thomas Hardy, D.H. Lawrence, Bram Stoker, and H.G. Wells.[12] These influences consisted of subtle yet pervasive structuring of human interactions with both each other and with nature. Their ubiquity is further evidence that Darwin was only a part, albeit a large one, of a larger pattern of social and intellectual change. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Darwin’s influence has also been felt extensively in science fiction, from Jules Verne to the Hunger Games.[13]

Beyond the Anglophone world, most of Darwin’s major works were quickly translated into other major languages, and this led to significant impacts around the world.[14] The literature of many nations – from Europe and Russia to the Arab-speaking world and China, just to name a few – also show profound impact of Darwin’s ideas.[15]

6. Visual art

The Cliffs at Etretat by Claude Monet (1885) (Wikimedia Commons; public domain).

While scholars have recognized Darwin’s impact on literature for many decades, his influence on the visual arts has become widely accepted only more recently. This influence had diverse aspects. One was the concept of beauty itself. Darwin’s theory of sexual selection and demonstration of the role of insects in ensuring pollination were practical, material, evolutionary theories of beauty. Darwin argued that in nature, beauty had no meaning beyond its contribution to survival and reproduction. The “source of beauty was natural laws, not a divine craftsman; the relativity of beauty was radically deep-seated, not merely a matter of individual taste; and the ultimate purpose of beauty was utilitarian and sexual, not universal and moral”[16]. This contributed to changes in ideas of artistic beauty and its significance.

Another influence was on artistic representations of nature.

“Old traditions in the representation of wild animals… were transformed by the new notions of interplay between different life forms. Many artists explored the darker aspects of ‘the survival of the fittest,, especially as they were projected in human terms. At the same time, however, Darwin’s sense of the vitality and the prolific beauties that paradoxically emerged from the grim war in nature inspired a new kind of painting of the natural world, where colour, pattern, movement and flux united animals with their surroundings.”[17]

Darwin’s effects can also be detected in landscape painting, with both British and American artists in the late nineteenth century becoming increasingly interested in detailing the dynamic forces revealed in geology over the lengthy history of the Earth implied by Darwin’s views.[18]

A number of French impressionist painters were influenced by Darwin’s work, including Paul Cézanne, Claude Monet, and Edgar Degas, and some French critics responded to early impressionist works by ascribing them to the pernicious side effects of Darwinism. Cézanne and Monet painted land and seascapes emphasizing their great age. Degas’ images of people stressed their similarities with animals.

“The abandonment of time-honored modes of painting and revered subject-matter seemed to go hand in hand with challenges to the structure of knowledge itself… Darwin’s publications were just one element in this story, but for many of his contemporaries they stood for the progress of rationalism and unfettered inquiry, and for a new relationship with the natural world. It was here that Darwin’s path intersected with that of the Impressionists, strengthening their identification with the increasingly secular, science-based culture around them…”[19]

7. Dystopia

“It was easy,” writes Levine with considerable understatement, “to use Darwinism to serve a multiplicity of antithetical purposes.” Darwin’s emphasis on imperfection as evidence of evolution was a major departure from the tradition of harmony emphasized by natural theology. Instead of all having been created for some higher, greater good, Darwin, as Levine puts it, saw “adaptation as contingent and incomplete, however breathtakingly wonderful it can be. He demonstrates disharmony, maladaptation, imperfection.” This was, perhaps understandably, seen by some as a prescription for a harsh and grim view of the present and future of humanity. In a world in which only the strong survive, then the dominance of the powerful over the weak was not just advantageous for those on the top of the socio-economic ladder, it was the proper and natural state of the world. This kind of thinking was part of the basis not only for the so-called “social Darwinism” of social scientists such as Herbert Spencer and industrialists like Andrew Carnegie, but also for the racist and imperialist policies of the late nineteenth century British empire and the mid-twentieth century Nazi regime, as well as the popularity of eugenics in the United States during the 1920s.

Such applications of Darwin’s ideas are now virtually unanimously condemned by scientists and politicians alike, but they are frequently cited even today by critics of evolution as evidence of its negative impact on society. Darwin himself largely rejected such extrapolations. Coming as he did from a liberal background, Darwin was personally on the progressive end of the socio-political spectrum of his time.[20] Although he did not doubt the “superiority” of white Europeans over various other racial groups, he did not think that this conclusion was an appropriate basis for social policy.

The question of whether the use of science and technology – whether evolution or nuclear energy – for destructive or “evil” purposes means that science itself is a potentially negative force is a persistent one for philosophers and politicians alike. Yet the fact that arguments made by Darwin can be used by people to justify horrific acts has absolutely no bearing on whether those arguments can help us to better understand the nature and history of life, which they clearly do. It does mean, however, that we should all be knowledgeable and vigilant enough to be able to question the application of all scientific ideas to areas beyond those for which they were originally formulated. Which brings us to the second major line of thought about Darwin’s impact and influence.

Universal Darwinism?

Although Darwin’s influence has extended, as just described, across the width and breadth of human thought over the past 150 years, there were many fields and areas of research that had considered, and then backed away from, strict application of natural selection. For example, in 1960 the noted historian of evolution John Greene wrote that if Darwin could “view the contemporary intellectual scene” he would find in the social sciences “evolutionary problems largely neglected and his own theory of social progress through natural selection in great disfavor. In the current emphasis on man’s uniqueness as a culture-transmitting animal,” Greene continued, Darwin might even “sense a tendency to return to the pre-evolutionary idea of an absolute distinction between man and other animals.”[21]

Greene’s assessment no longer holds. The past half-century has seen a dramatic expansion of the application of natural selection to virtually every area of human activity, especially those that had deemphasized it as an adequate explanatory approach just a few years before. As Hösle and Illies note:

“It has even been argued that Darwinism is itself a philosophical theory, since it seems to be about ‘being in general’… wherever we have a plurality of entities reproducing themselves and vying for scarce resources, we have a Darwinian situation – the entities may be organisms competing for food, languages competing for speakers, or scientific theories competing for intellectuals supporting them…”[22]

Much of the new fondness for natural selection as an essentially “universal” explanation for all features of living things – human and otherwise – can be traced to the explication in the late 1970s of the field of sociobiology by the late great entomologist and evolutionary biologist Edward O. Wilson, and it has been particularly conspicuous in psychology and the social sciences.[23] Unlike the historical influences described above, however, this influence of Darwin is still in many respects novel and still frequently highly controversial. It is the subject of a large and growing literature, and I will here only touch on a few of its purported accomplishments.

1. Psychology

Although not anti-Darwinian, the schools of thought that dominated psychology during most of the twentieth century (Freudianism, Jungianism, etc.) emphasized non-genetic, “environmental” factors as much as or more than inherited factors on which natural selection might act. In contrast, modern “evolutionary psychology” attempts to explain virtually all human (and non-human) mental phenomena – from aggression and love to religion and infidelity – as the results of (mostly past) natural selection. The mind is the way it is, argue advocates of this view, because natural selection built it that way.[24]

2. Literature

As summarized above, Darwin’s work had enormous impact on literature in the English-speaking world and beyond. According to a growing school of literary critics, not only is post-Darwinian fiction – such as the novels of Conrad or the poems of Frost – influenced by evolutionary themes, but human relationships described in essentially all literature, no matter when it was written, can be analyzed and understood as results of natural selection.[25] For example, the cuckholdry and jealousy of Othello is ultimately the result of the differing reproductive demands on males and females and of biologically mandated competition for mates. The hubris of Macbeth and emotional turmoil of Hamlet are similarly the result of genetically-determined predispositions – albeit more or less affected by their various environmental contexts – for particular behaviors.

3. International relations

In these times of international turmoil and uncertainty, it is perhaps not surprising that the new Darwinism has turned its attention to natural selection as a potential explanation for patterns of relationships among peoples and nations. In some cases, such analyses are little more than simple analogies between societal security problems and characteristics evolved in non-human nature, which are used to shed light on strengths or weaknesses of particular societal security arrangements or systems. Other analyses focus on how actual evolutionary processes, such as the development of the ancestral mind and the emergence of human social structures, may be affecting the security environments today. Still others attempt to use tools that were developed for evolutionary and ecological studies – such as demographic and epidemiological models – to address security problems. In such analyses, war and peace, just to take one example, are explained as results of natural selection for the survival of individuals or groups, in addition to, or instead of, the results of purely non-genetic, “social” factors.[26]

4. Evolutionary medicine

A phylogenetic, or evolutionary, tree depicting the relationships among the varied strains of the COVID-19 virus sampled between Dec. 2019 and Jan. 2022. These results demonstrate that the late 2021 Omicron variant is much more closely related to mid-2020 forms of COVID-19 than to the Delta varient that dominated infections in the second half of 2021. Image is a screen capture from Nextstrain.

Since the 1980s, a field variously known as “evolutionary” or “Darwinian medicine” – the notion that disease can be understood and treated from an explicitly Darwinian (i.e., evolution driven mainly by natural selection) point of view – has grown from an exotic suggestion to the mainstream. An evolutionary perspective on medicine addresses not just treatments, but also the origin of diseases and why particular treatments do (or don’t) work. Topics in which evolutionary medicine has particularly flourished include the evolution of bacteria and viruses (e.g., COVID-19), and of their resistance to antibacterial and antiviral drugs; inherited or partly-inherited conditions such as obesity and high blood pressure; and diseases such as cancer and mental illness. It has its own robust research literature and is now taught at many if not most major medical schools. (Ironically, many surveys of American physicians suggest that a much larger proportion do not fully accept Darwinian evolution than in any other biological discipline. This may now at last begin to change.)[27]

What Darwin Did

One of the most common misconceptions about science is that it is mainly about “truth.” Science is, of course, about finding out what the world is “really” like, and we have excellent reasons for thinking that science has succeeded in determining many aspects of this reality with high degrees of confidence. But as much or more than such conclusions, however, science is about a method of searching for them. All scientific conclusions, even those – such as evolution by natural selection – that we effectively treat as “true” because they are supported by such overwhelming evidence, are only provisional and can be rejected if they are shown not to agree with enough observations about nature. The best and most successful scientific ideas are therefore not just those that appear to be correct – because this can change – but those that lead to further research, because this is the only way that science can continue to approach, even if it never reaches, the truth.

In this context, evolution by natural selection – Darwinism – is one of the best and most successful scientific ideas ever proposed. What Darwin did goes far beyond his specific explanations for particular observations about living things – although many of these are so immensely useful and satisfying that we can scarcely imagine any other. What he did was produce – almost single-handedly – a way of seeking and evaluating such explanations. The increasing expansion in applications of Darwinian thought to the social sciences and humanities, no less than their indisputable influence over the 150 years since On the Origin of Species, is clear evidence (as though more were needed) of how profoundly this example of human thought continues to shape the world it sought to explain.

References and further reading

Allmon, W.D., 2011, Why don’t people think evolution is true? Implications for teaching, in and out of the classroom. Evolution: Education and Outreach, 4: 648-665.

Barash, D.P., and N.R. Barash, 2005, Madame Bovary’s ovaries. A Darwinian look at literature. Delacorte Press, New York, 262 p.

Barkow, J.H., L. Cosmides, and J. Tooby, eds., 1994, The adapted mind: Evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture. Oxford University Press, New York, 688 p.

Bedell, R., 2009, The history of the Earth: Darwin, geology, and landscape art. In Endless forms. Charles Darwin, natural science and the visual arts. Donald, D., and J. Munro, eds., Yale University Press, New Haven, pp. 49-80.

Beer, G., 1983, Darwin’s plots. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 303 p. (3rd edition, 2009)

Buss, D., 2019, Evolutionary psychology: The new science of the mind. 6th ed. Routledge, New York, 518 p.

Carroll, J., 2004, Literary Darwinism. Evolution, human nature, and literature. Routledge, New York, 276 p.

Crook, P., 1994, Darwinism, war, and history: The debate over the biology of war from the “Origin of Species” to the First World War. Cambridge Univ Press, 318 p.

Cziko, G.A., 1997, Without miracles: Universal selection theory and the second Darwinian revolution. Bradford Books/MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 399 p.

Dennett, D., 1995, Darwin’s dangerous idea. Simon and Schuster, New York, 586 p.

Desmond, A., and J. Moore, 2009, Darwin's sacred cause: Race, slavery and the quest for human origins. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, New York, 448 p.

Dobzhansky, T., 1973. Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. The American Biology Teacher, 75(2): 87-91.

Donald, D., 2009, The ‘struggle for existence’ in nature and human society. In Endless forms. Charles Darwin, natural science and the visual arts. Donald, D., and J. Munro, eds., Yale University Press, New Haven, pp. 81-100.

Donald, D., and J. Munro, eds., 2009, Endless forms. Charles Darwin, natural science and the visual arts. Yale University Press, New Haven, 344 p.

Elshakry, M., 2014, Reading Darwin in Arabic, 1860-1950. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 448 p.

Faggen, R., 1997, Robert Frost and the challenge of Darwin. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 363 p.

Gianquitto, T., and L. Fisher, eds., 2014, America’s Darwin. Darwinian theory and U.S. literary culture. University of Georgia Press, Athens, 401 p.

Glendenning, J., 2007, The evolutionary imagination in late-Victorian novels. An entangled bank. Ashgate, Aldershot, UK, 225 p.

Glick, T.F., M.A. Puig-Samper, and R. Ruiz, eds., 2001, The reception of Darwinism in the Iberian world: Spain, Spanish America and Brazil. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 295 p.

Glick, T.F., and E. Shaffer, eds., 2014, The literary and cultural reception of Charles Darwin in Europe. Volume 3. Bloomsbury, London, 386 p.

Graham, P.W., 2008, Jane Austen and Charles Darwin. Naturalists and novelists. Routledge, New York, 216 p.

Greene, J.C., 1961, Darwin and the modern world view. Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, 141 p.

Hösle, V., and C. Illies, eds., 2005, Darwinism and philosophy. University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, Indiana, 392 p.

Kendall, R., 2009, Monet and the monkeys: the Impressionist encounter with Darwinism. In Endless forms. Charles Darwin, natural science and the visual arts. Donald, D., and J. Munro, eds., Yale University Press, New Haven, pp. 293-318.

Leatherdale, W., 1983, The influence of Darwinism on English literature and literary ideas. In The wider domain of evolutionary thought. D. Oldroyd and I. Langham, eds., D. Reidel Publishing Co., Dordrecht, pp. 1-26.

Levine, G., 1988, Darwin and the novelists. Patterns of science in Victorian fiction. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 319 p.

Morton, P., 1984, The vital science. Biology and the literary imagination, 1860-1900. George Allen & Unwin, London, 257 p.

Nesse, R.M., and G.C. Williams, 1996, Why we get sick: The new science of Darwinian medicine. Vintage, Place, 304 p.

O’Hanlon, R., 1984, Joseph Conrad and Charles Darwin: The influence of scientific thought on Conrad's fiction. Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, NJ, 188 p.

Ruse, M., ed., 2009, Philosophy after Darwin. Classic and contemporary readings. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 580 p.

Sagarin, R.D., and T. Taylor, eds., 2008, Natural security. A Darwinian approach to a dangerous world. University of California Press, Berkeley, 289 p.

Sharp, P., 2014, Darwinism. In The Oxford handbook of science fiction. R. Latham, ed., Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 475-485.

Smith, J., 2009, Evolutionary aesthetics and Victorian visual culture. In Endless forms. Charles Darwin, natural science and the visual arts. Donald, D., and J. Munro, eds., Yale University Press, New Haven, pp. 237-252.

Somit, A., and S.A. Peterson, 1997, Darwinism, dominance, and democracy: The biological bases of authoritarianism. Praeger, Greenwich, CT, 160 p.

Stamos, D.N., 2003, The species problem. Biological species, ontology, and the metaphysics of biology. Lexington Books, Lanham, MD, 380 p.

Stearns, S.C., and R. Medzhitov, 2015, Evolutionary medicine. Sinauer Associates/Oxford University Press, Cary, NC, 328 p.

Thayer, B.A., 2004, Darwin and international relations. On the evolutionary origins of war and ethnic conflict. University of Kentucky Press, 425 p.

Thompson, W.R., ed., 2001, Evolutionary interpretations of world politics. Routledge, NY, 362 p.

Vucinich, A., 1988, Darwin in Russian thought. University of California Press, Berkeley, 468 p.

Wainwright, M., 2008, Darwin and Faulkner’s novels. Evolution and southern fiction. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 243 p.

Wilson, E.O., 1975, Sociobiology. The new synthesis. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 697 p.

Wilson, E.O., 1978, On human nature. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 260 p.

Wittgenstein, L., 1922, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 207 p.

Wright, R., 1994, The moral animal: Why we are the way we are: The new science of evolutionary psychology. Pantheon, New York, 467 p.

Xiaoxing Jin, 2020, The evolution of evolutionism in China, 1870–1930. Isis, 111(1): 46-66.

Footnotes

[1] Beer (1983: 2).

[2] See, for example, Allmon (2011).

[3] Hösle and Illies (2005: 1-2).

[4] Morton (1984: 1).

[5] Dobbs, D., 2017, Survival of the prettiest. The New York Times, Sept. 18.

[6] Levine (1988: 9).

[7] Levine (1988: 1).

[8] Levine (1988: 14-15).

[9] Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote in 1922 that “Darwin’s theory has no more relevance for philosophy than any other hypothesis in natural science” (Wittgenstein, 1922: 4.1122).

[10] Levine (1988: 94).

[11] Good introductions to both the history and current state of this complicated topic are the volumes edited by Hösle and Illies (2005) and by Ruse (2009). Both demonstrate that Darwin’s influence extends into virtually all areas of modern philosophy.

[12] See, for example, Beer (1983); Leatherdale (1983); Morton (1984); Levine (1988); Faggen (1997); Carroll (2004); Glendenning (2007); Graham (2008); Wainwright (2008); and Gianquitto and Fisher (2014).

[13] See Sharp (2014).

[14] According to Darwin Online, “The Origin of Species was translated into eleven languages in Darwin's lifetime and more than thirty-five to date making it the most widely translated science work in history. The Descent of Man was translated into eight languages in Darwin's time and perhaps twenty at the present. Only his taxonomy of barnacles and some of the shorter publications have never been translated.”

[15] See, for example, Vucinich (1988); Glick et al. (2001); Elshakry (2014); Glick and Shaffer (2014); Xiaoxing Jin (2020)

[16] Smith (2009: 239).

[17] Donald (2009: 81).

[18] Bedell (2009).

[19] Kendall (2009: 316).

[20] Desmond and Moore (2011).

[21] Greene (1961: 130).

[22] Hösle and Illies (2005: 4).

[23] See Wilson (1975). For introductions to this sprawling and controversial topic, see Dennett (1995); Cziko, (1997); Wikipedia; and Universal Selection.

[24] Wilson (1978; second edition 2004) is a foundational book on the role of natural selection in shaping human psychology and all other traits. An excellent current textbook on the subject is Buss (2019). An older but more accessible summary is Wright (1994).

[25] Barash and Barash (2005).

[26] Useful explorations of this complex topic include Somit and Peterson (1997); Thompson (2001); Thayer (2004); and Sagarin and Taylor (2008).

[27] The classic introduction to the field of evolutionary medicine is Nesse and Williams (1996). An excellent recent comprehensive summary is Stearns and Medzhitov (2015).