PRI announces discovery of feathered brachiopod fossil

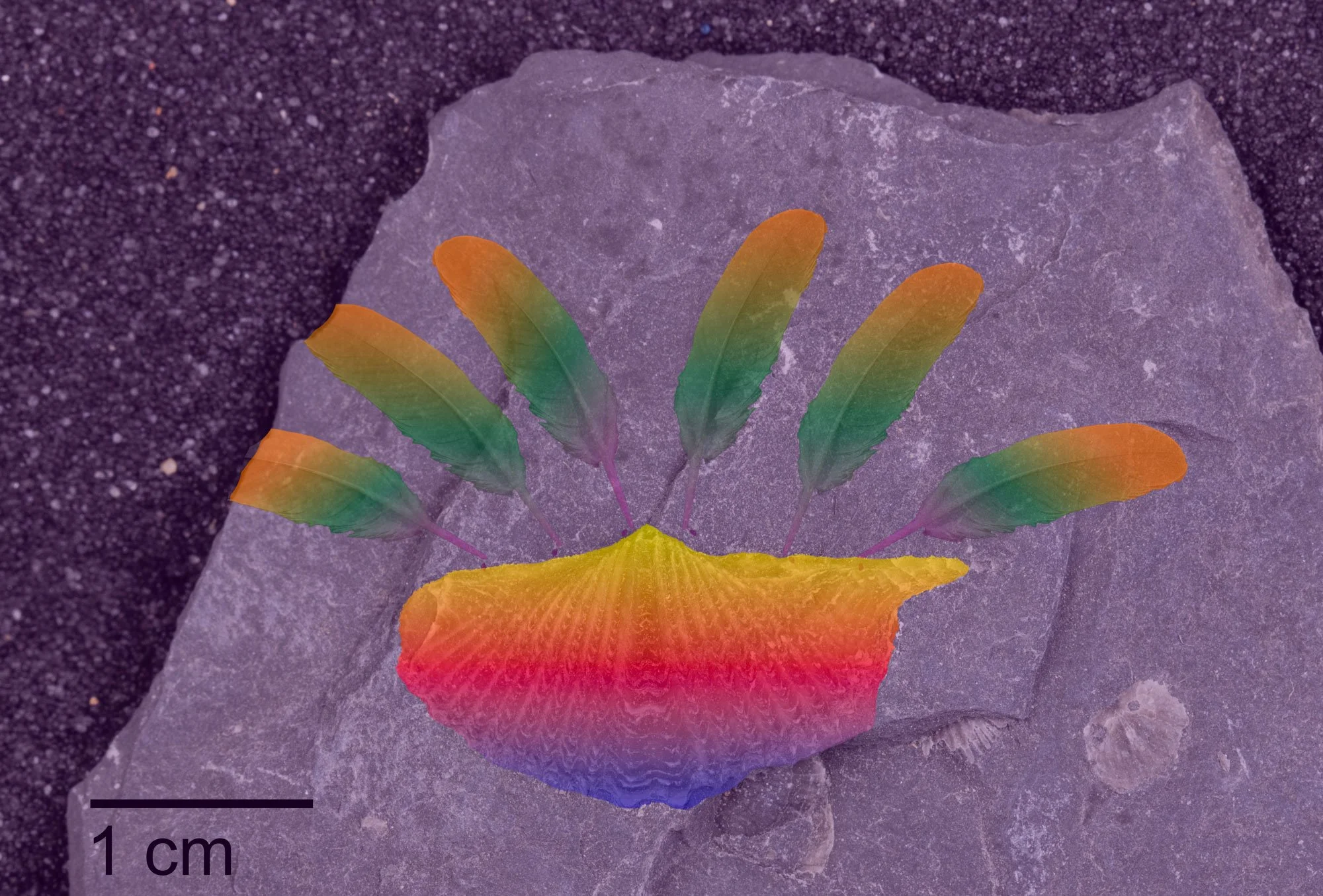

Newly discovered feathered brachiopod from the Middle Devonian Moscow Formation (Hamilton Group) of Tompkins County, New York.

ITHACA, NEW YORK, April 1, 2023 — for immediate release

The humble brachiopod ruled the Paleozoic seafloor for millions of years. Prior research has shown that their days were full of activity. They occasionally opened their valves by a millimeter or two to filter tiny bits of food from the water or closed them when startled by the gentle wake of a passing worm. In some cases, this cycle of activity may have happened two or three times in a single week.

After nearly two centuries of intensive study, paleontologists thought that they had learned all the brachiopod’s secrets. A recent fossil discovery, however, is painting a startling new picture of the lifestyles of brachiopods and their relationships to other animals.

While searching the vast “behind the scenes” fossil collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, museum staff discovered a most unusual brachiopod specimen at the back of a drawer that had not been explored for over two decades. The specimen shows faint traces of structures that look very much like the feathers of modern birds. The case that these structures are feathers is made even stronger when the specimen is viewed under ultraviolet (UV) light. The UV light causes ancient pigments in the feathers and the shell itself to fluoresce, revealing the original coloration patterning of this remarkable fossil.

Shining ultraviolet light on the specimen revealed preserved coloration patterns on the shell and feathers of the newly discovered fossil brachiopod.

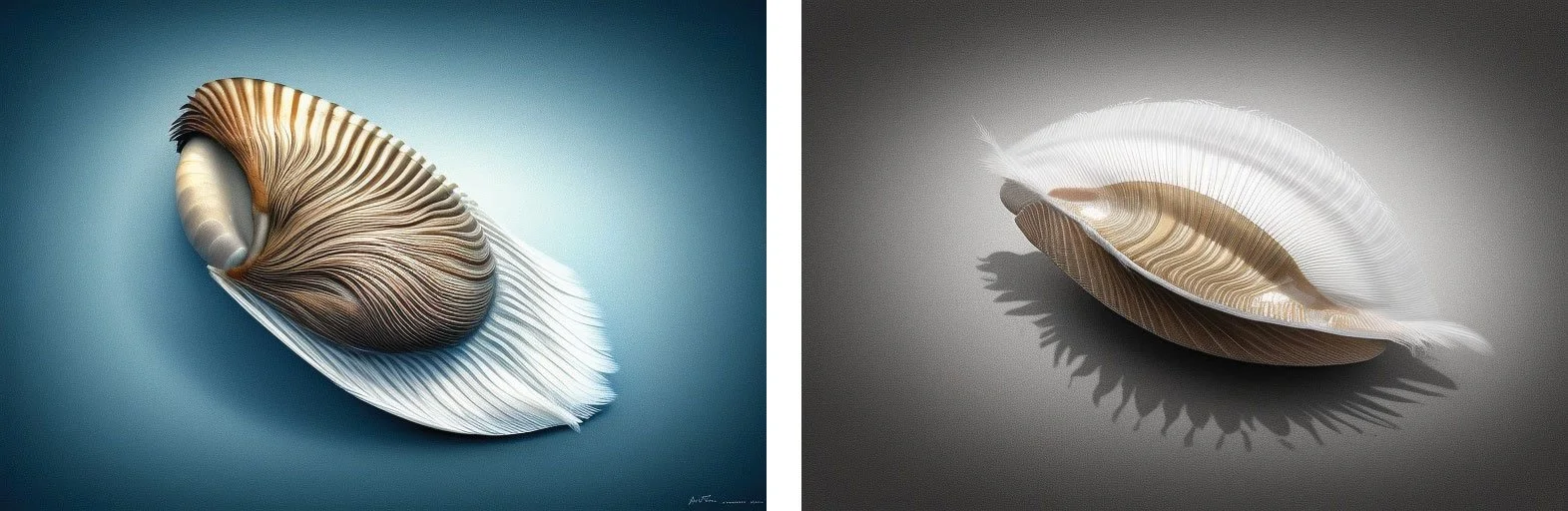

What did the brachiopod, which has been assigned the scientific name Pteroconcha icara, do with its feathers? Until this discovery, paleontologists thought that feathers first evolved in dinosaurs for keeping warm, and were only later co-opted by birds—their evolutionary descendants—for flight. Having little need to stay cozy, paleontologists are in near universal agreement that P. icara used its feathers to soar through the air. What is less certain is how the feathers were arranged relative to the shell as P. icara rested on the seafloor. This uncertainty caused several heated and sometimes acrimonious debates at the 173th Annual Meeting of the Royal Associational of Brachiopodologists conference in Lucerne, where the new discovery was announced late last Month. Around half of participants accepted the “feathers fan down” resting hypothesis, which would have favored stability on soft muds. The remainder promoted the “feathers fan up” hypothesis, which would have helped the brachiopod gain lift as it shot through the ocean depths into sky above.

The two competing hypotheses for the resting position of Pteroconcha icara. Left: reconstruction showing the “feathers fan down” hypothesis. Right: the “feathers fan up” hypothesis. Artwork by Stable Diffusion.

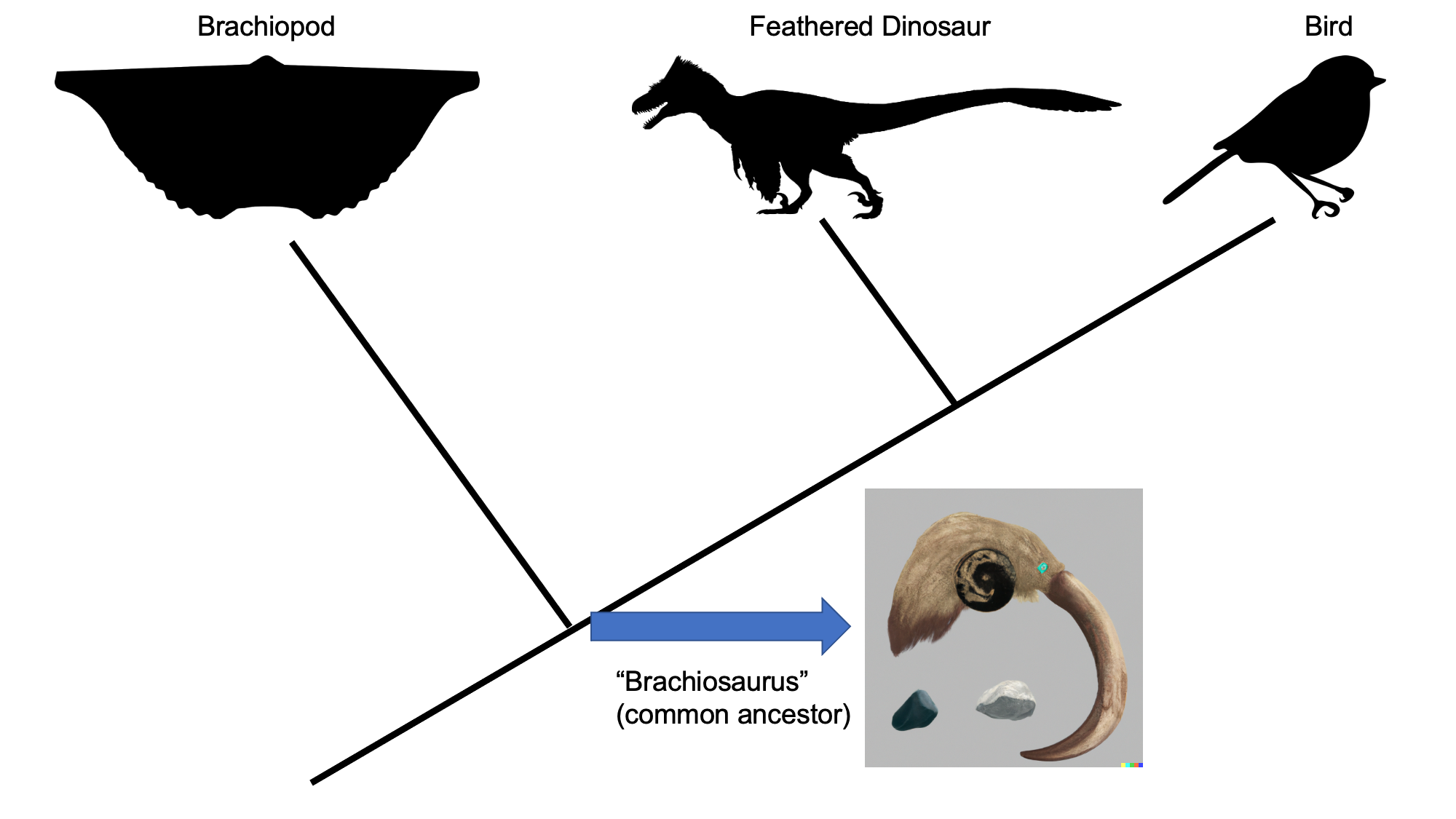

The presence of feathers in this brachiopod begs the question of evolutionary origins. The new discovery suggests two possibilities: either 1) feathers evolved independently twice, or 2) dinosaurs and brachiopods evolved from a close common ancestor that also had feathers. The philosophical principle of Occam’s razor – which supports simpler explanations over more complex ones – suggests that the second possibility more likely. The invertebrate paleontologists involved in the study have termed this as yet undiscovered common ancestor “Brachiosaurus” pending review of the taxonomic literature to determine if this scientific name is unused and available.

Cladogram, or evolutionary tree, depicting relationships between brachiopods, feathered dinosaurs, and birds. The common ancestor of all three groups has been dubbed Brachiosaurus by invertebrate paleontologists.

Reconstruction of the common ancestor dubbed Brachiosaurus, which has features of both brachiopods and feathered dinosaurs. Artwork by Dall-E.

Asked to comment on the new discovery, PRI paleontologist Jonathan Hendricks—who was not involved in the study—added, “Ancient brachiopods didn’t have feathers and didn’t fly. They were barely alive. They aren’t at all closely related to dinosaurs, which honestly is a good thing.”

Paleontologists are aflutter about this new fossil and several textbook publishers are already planning revised editions to incorporate mention of Pteroconcha icara, the brachiopod that may have flown too close to the sun.

###

We hope you enjoy this April Fool’s Day by visiting the Museum of the Earth and the (unfeathered) brachiopods in our new temporary exhibit, NY Rocks! Ancient Life of the Empire State.